|

Charles Lindbergh – Aviator and Celebrity by David Langley |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Page | Airmen Index | ||

|

|||

| The first true American celebrity was neither a politician like Teddy Roosevelt, nor a movie star like Mary Pickford, nor a sportsman like Babe Ruth. While Roosevelt achieved his fame in a few arenas of life, he did so before the advent of radio, and Pickford and Ruth were famous in just one arena. Instead, the first American celebrity was a flier—Charles A. Lindbergh. After all, he was the son of a multi-term congressman; his trans-Atlantic flight was a stunning feat of technology; he married into a famous political family; his eldest son’s kidnapping and murder led to “the trial of the century”; his political fortunes rose and fell and then rose again in the 1940s and 1950s; and in his final decades he became an advocate for one of the late 20th century’s most respected causes—environmental conservation. | |||

|

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was the son of Charles August and Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh. Charles August was a lawyer, and Evangeline was a high school science teacher. On February 4, 1902, baby Charles was born in a three-story brownstone at 1220 West Forest, in Detroit, Michigan, the home of Mrs. Lindbergh’s father, a medical doctor. Six weeks later, the Lindberghs returned to their own home in Little Falls, Minnesota.

In November of 1906, Mr. Lindbergh was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Minnesota’s 6th District, where he served until 1917. (According to Susan Hertog’s fine biography of Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the former congressmen then “hustled real estate in Florida but barely managed to survive one day at a time. In 1924, he died of a brain tumor in Little Falls, homeless, penniless, broken, and alone.”1)In the summer of 1912, young Charles attended an air race, where he became fascinated with airplanes. Six years later, he graduated from Little Falls High School. In the fall of 1920, Lindbergh started attending the University of Wisconsin to study engineering. However, in February of 1922, the university dismissed him because of poor grades.2 Two months later, he moved to Lincoln, Nebraska, and enrolled in a local flight school run by the Nebraska Aircraft Corporation. That same year, after years of being disaffected from her husband, Lindbergh’s mother began teaching at Cass Technical High School in Detroit, and did so for another twenty years. During the spring and summer of the next year, Lindbergh began barnstorming his way across the midwestern United States in a Curtiss JN-4 that he purchased in 1923 for five hundred dollars.3 In March 1924, he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Service and began further pilot training. After that he flew as a mail pilot for the Robertson Aircraft Corporation, flying a Liberty powered de Havilland DH-4.4

Back in 1919, a New York hotel owner named Raymond Orteig had created the Orteig Prize, offering $25,000 to the first person to fly solo and non-stop from New York to Paris. In the fall of 1926, Lindbergh began planning to capture the prize and started looking for investors to help finance the design and construction of an airplane suited for such a flight. Finding nine investors in Saint Louis, he accumulated over $15,000 and then settled on the Ryan Aeronautical Company in San Diego, California as his plane builder, with the aircraft to be powered by a Wright Whirlwind engine.5 The company completed construction of the airplane in April of 1927. To honor his midwestern financiers, he named his plane The Spirit of St. Louis and started flight testing. After completing the tests, Lindbergh leapfrogged his way across the United States from San Diego to St. Louis and then to New York in twenty-one hours, forty-five minutes of overall flight time.6 He arrived at Curtiss Field, Long Island, New York on May 12. He later transferred his plane to nearby Roosevelt Field, in Garden City. This cross-country trip reinforced Lindbergh’s confidence that his plane could withstand the rigors of a trans-Atlantic flight. By itself, the transcontinental flight would have been a big story at any other time, but it garnered hardly any attention by the newspapers. However, his competitors at Roosevelt field surely took notice, now considering him a serious contender for the race to Paris.

On May 20, 1927, just after 7:50 a.m., New York time, Lindbergh took off for Paris, barely clearing the trees and power lines at the end of the grass runway. Lindbergh carried with him just five sandwiches, drinking water, some maps and charts, and a few other needed items. Deciding that a parachute would be useless equipment over the Atlantic, he did not carry one. On May 21, just after 10:50 p.m., Paris time, Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget Airport, just south of Paris. Over 150,000 adoring Parisians stormed his airplane,7 forcing the local police to fight them off and escort both Lindbergh and the plane to a hangar for their protection. In a later account of the flight, he described the aftermath of his landing: “The engine log and navigation log of ‘The Spirit of St. Louis’ were stolen by some member of the crowd . . . .” To create chapter headings for this account, he had to rely on just “performance curves and other records.”8 From Le Bourget, Lindbergh was rushed to the home of the American ambassador in downtown Paris and then spent three weeks being wined and dined in France, Great Britain, and other European countries. In the coming days, Lindbergh became the most photographed, most filmed, and most famous living person on earth.

On June 10, 1927, Lindbergh arrived in the United States on board the cruiser USS Memphis. While steaming up Chesapeake Bay, the ship was accompanied by four destroyers, two U.S. Army blimps, and 40 airplanes. Again captured on film, Lindbergh modestly disembarked from the ship at the Washington Navy Yard on June 11. At the White House, he received from President Calvin Coolidge the Congressional Medal of Honor and the first-ever Distinguished Flying Cross. On June 13, Lindbergh was greeted by over four million people at events honoring him in New York City. After other public functions, he began an 82-stop tour of the United States, landing at least once in all 48 states. Late in the same year, he flew to South America as a goodwill representative for the U.S.A. While visiting Dwight Morrow, the U.S. ambassador in Mexico City, he met the diplomat’s 21-year old daughter, Anne. |

|

Anne had been born in June of 1906 in Englewood, New Jersey to the ambassador and Elizabeth Morrow. Anne’s childhood education emphasized much reading and writing, especially poetry. In June 1924, she graduated from the Chapin School for Girls, an elite private school in New York City. In May 1928, she graduated from Smith College, receiving two literary awards. Although Lindbergh was attracted to Anne rather quickly, it took the famous flier ten months to ask her for a date. On just their third date, however, he proposed marriage, and she accepted. |

|

In 1928, Lindbergh donated his famous airplane to the Smithsonian Institution. The plane now hangs from the ceiling of the main foyer of the National Air and Space Museum. According to the publication Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft, reprinted at NASA’s official website, Lindbergh’s plane “popularized the monoplane configuration in America and marked the beginning of the decline of the biplane.”10

In May of 1929, Lindbergh and Anne Morrow were married at her parents’ estate. Thirteen months later, in June of 1930, their first child, Charles, Jr., was born. Lindbergh now was not only a famous flier, but also newly married to a politician’s pretty daughter and the father of—many people assumed—a future aviator. However, celebrity did not sit well with the shy young man from small town Minnesota and his new bride. Therefore, in 1931, to escape media attention, the couple built a secluded home in East Amwell, in northern New Jersey. The Lindberghs also used flying as a way to escape the media—at least until their return from a trip. Together, they began a series of flights that established them as America’s premier flying couple. An article from History Today neatly describes a few of these expeditions: |

| The Lindberghs were a model modern couple, at the cutting edge of technological developments. Together they pioneered the use of aerial photography as an aid to archaeologists, focusing on Central American sites. When they flew to East Asia in 1931 scouting for US-Chinese air routes, Anne served as co-pilot, navigator and radio operator. The mission was part of Lindbergh's campaign on behalf of commercial aviation.11 |

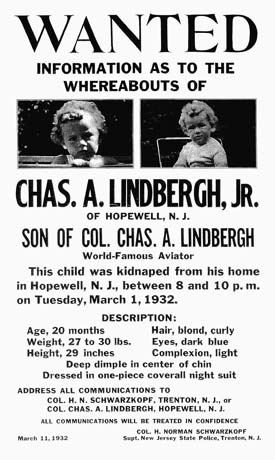

| Despite the pleasures of joint flights, trouble still found the Lindberghs back at their country home. On March 1, 1932, Charles Jr. was kidnapped. An anonymous note demanded a $50,000 ransom to retrieve the child. Several follow-up notes assured the Lindberghs that the baby was alive. However, in May a truck driver found the dead baby not far from the Lindberghs’ home. Meanwhile, ransom money had started turning up around and in New York City. By September, police had a suspect: Richard Bruno Hauptmann, a German immigrant living in the Bronx and working as a carpenter. |

|

|

The enormity of the crime, the advent of radio as a communication vehicle, and the Lindbergh couple’s celebrity status generated enormous media attention. Hauptmann’s trial began in 1934. Despite flaws in the investigation process and criminal attempts to swindle the Lindberghs, the evidence against Hauptmann was overwhelming. After a six-week trial, he was found guilty and sentenced to death. |

|

Despite the closure caused by Hauptmann’s conviction, reporters continued to view the Lindberghs as celebrities and continued to hound them. As well, dangerous threats from disturbed persons came often against the famous couple’s second son, three-year old Jon. One day in 1935, an upsetting event convinced the couple to abandon life in the United States. Susan Hertog describes the event as follows: “[R]eporters stalked Jon on his way to school. Sideswiping the Morrows’ car, they pushed it off the road and pulled open the doors to take the boy’s picture. Within hours, Charles and Anne decided to leave America.”12 The family moved to Kent in the United Kingdom and later to France.

In April 1936, at the New Jersey State Prison in Trenton, Hauptmann died in the electric chair. In the same year, at the request of the American ambassador to Germany, Lindbergh visited that country to inspect its aviation industry. Anne accompanied him. While there, the Lindberghs also attended the summer Olympic Games in Berlin. As noted on the official PBS website, the couple came to unsettling conclusions about Germany’s preparations for war: |

| [Lindbergh] was soon convinced that no other power in Europe could stand up to Germany in the event of war. "The organized vitality of Germany was what most impressed me: the unceasing activity of the people, and the convinced dictatorial direction to create the new factories, airfields, and research laboratories . . . ," Lindbergh recalled in Autobiography of Values. His wife drew similar conclusions.13 |

| The Lindberghs’ visit to Germany was controversial, but Charles (and the American government) wanted to learn as much as possible about Nazi Germany’s aviation build-up, so he returned to Germany in 1937 and 1938. In October of 1938, he received the Order of the German Eagle from Hermann Goering, Hitler’s personally appointed head of the Luftwaffe. Lindbergh saw nothing wrong with accepting the medal, but the increasingly obvious nature of the Nazi regime led many observers to criticize the flier for being at least naďve or, at worst, enamored of Hitler and anti-Semitic. Among those who criticized the flier was his mother-in-law, Betty Morrow. |

|

|

The Germans invaded Poland in September 1939 and, by June 1940, had occupied much of France. As the war continued in Europe, the Lindberghs returned home. The pressures of public life, the constant moves, and Charles’ domineering personality conspired to cause marital problems as well. Nevertheless, Anne remained with Charles even as he threw himself into the intense politics of pre-Pearl Harbor America.

As with many others in America, both left and right, Lindbergh opposed America’s entry into the war unless attacked. In 1941, he became a leading spokesman for the America First Committee. During a speech in Des Moines, Iowa, he decided to criticize specific people and groups, saying that they needlessly sought to embroil the United States in the war: |

|

The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish, [sic] and the Roosevelt administration.

Behind these groups, but of lesser importance, are a number of capitalists, Anglophiles, and intellectuals who believe that the future of mankind depends upon the domination of the British Empire. Add to these the Communistic groups who were opposed to intervention until a few weeks ago, and I believe I have named the major war agitators in this country.14 |

| President Franklin Roosevelt attacked Lindbergh for his views, so the flier resigned his officer’s commission in the U.S. Army Air Corps. |

| After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Lindbergh tried to rejoin the military, but Roosevelt—still angry over the flier’s pre-war stance—blocked the request. Instead, Lindbergh became a private consultant for Henry Ford who—like many other car builders—was converting automobile plants to aviation plants for the war effort. In 1943, Lindbergh went to the South Pacific as a civilian “observer.” However, while there, he flew more than 50 combat missions, often in Lockheed P-38 Lightnings; shot down at least one opponent; and taught other pilots how to conserve fuel and extend the range of their aircraft. |

|

|

After World War II, the U.S. government asked Lindbergh to visit Germany again (Franklin Roosevelt, now dead, had been succeeded by Harry Truman). While there, the flier’s main job was to study the Germans’ V-2 rocket program. After Dwight Eisenhower succeeded Truman as president, he reinstated Lindbergh’s officer’s commission, and Lindbergh eventually retired from the military as a general in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. In 1954 Lindbergh published The Spirit of St. Louis, his personal account of his famous 1927 flight to Paris; the book won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.15 He also became a consultant for Pan American World Airways and Boeing Aircraft.

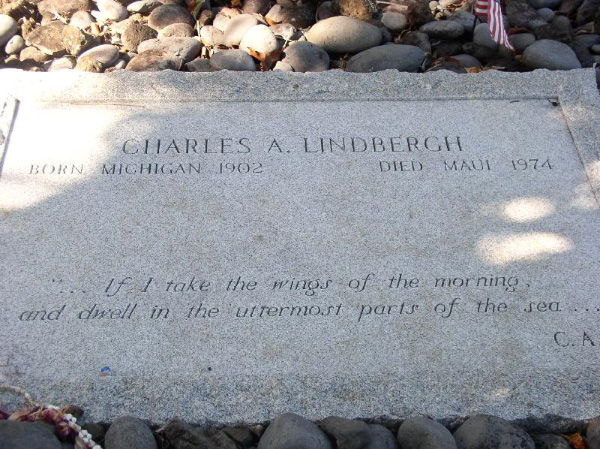

In 1964, Lindbergh published an article in Reader’s Digest entitled “Is Civilization Progress?” The article asserted that humans can survive and succeed only if we find a way to balance the desire for advancing technology with the need for a livable planet. He also worked to protect tribes in the Philippines and Africa and to protect the humpback whale and blue whale. Along with other conservationists, he opposed development of an American supersonic transport, believing that the high-powered engines needed for such a craft would aggravate air-pollution levels worldwide. In October of 1972, Lindbergh learned that he had cancer. Despite radiation treatments, the flier died on August 26, 1974. Having settled in Hawaii in the late 1960s, he was buried in the Palapala Ho'omau Church Cemetery, in the village of Kipahulu on the island of Maui.

Anne Lindbergh lived until February of 2001. Building on her strong writing skills acquired in high school and college, she had published several best-selling books. Two of her most famous are North to the Orient (1935) and Listen! The Wind (1938). These works are based upon the aviation trips that Charles and she took in the 1930s. A later major work is Gift from the Sea (1955), a collection of eight essays. In recent years, DNA tests and other evidence such as letters have shown that Lindbergh fathered several children out of wedlock by three European women. According to an NBC television report, Lindbergh may have done so because of long-lasting, unresolved grief over the death of his firstborn child.16 Charles and Anne Lindbergh themselves had five surviving children: Jon, Land, Anne, Scott, and Reeve. Jon, born in 1932, is an oceanographer and deep-sea diver. Land, born in 1937, runs a cattle ranch in Montana. Anne, who lived from 1940 to 1993, was principally an author of children’s books. Scott, born in 1942, lives and works in Brazil. Reeve, the youngest, was born in 1945 and is a well-known writer and honorary chairman of the Lindbergh Foundation. In these accomplished people, the Lindbergh legacy lives on.

|

End Notes:

|

1. Susan Hertog. Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life. (New York: Talese/Doubleday, 1999.), 18. 2. A. Scott Berg. Lindbergh (New York: The Berkley Publishing Group, 1998) 60. 3. Charles A. Lindbergh. We. (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1927). 39. 4. Charles A. Lindbergh. The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Carles Scribner's Sons, 1953.) 5. 5. Ibid. 74. 6. Ibid. 504. 7. A. Scott Berg. 128. 8. Ibid. x. 9. Ibid. 154 - 155. 10. Laurence K. Loftin, Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft. Chapter 4 - Design Revolution, 1926-39, Monoplanes and Biplanes. www.hq.nasa.gov/pao/History/SP-468/contents.htm 11. Goliath, Business Knowledge on Demand. Between Heaven and Earth: Lindbergh: goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-7372150/Between-heaven-and-earth-Lindbergh.html (January 1, 2008.) 12. Susan Hertog. 278. 13. "Fallen Hero; Charles Lindbergh in the 1940s." Lindbergh www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/lindbergh/index.html PBS, American Experience. 1999. 14. "Des Moines Speech." Lindbergh www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/lindbergh/filmmore/reference/primary/desmoinesspeech.html PBS, American Experience. 1999. 15. "The Pulitzer Prizes: Biography or Autobiography." www.pulitzer.org/bycat/Biography-or-Autobiography 16. Keith Miller. "The Secret Lives of Charles Lindbergh." www.bing.com/videos/watch/video/the-secret-lives-of-charles -lindbergh/6ib0ufz NBC Today. (July 31, 2005) |

| The Author David Langley is an Adjunct Instructor of English at SUNY Rockland in Suffern, NY. |

Return to Airmen Index

© The Aviation History On-Line Museum. All rights reserved.

Created January 4, 2010. Updated Janury 26, 2013.