|

Navy-Curtiss NC-4 Flying Boat - USA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Page | Aircraft Index | ||

|

|||

| Crew of the NC-4 from left consists of Lt. E.F. Stone, USCG pilot; Chief Machinist's Mate (Air) E.S. Rhoades, USN Engineer; Lt. W.K. Hinton, USNRF Pilot; Ens. H.C. Rodd, USNRF Radio Operator; Lt. J.L. Breese, USNRF Reserve Engineer; LT. Comdr. A.C. Read, USN Commanding Officer and Navigator; and Captain Jackson of the base ship Melville. | |||

|

Once the accomplishment of powered flight became a reality, the urge was inevitable to improve upon the speeds, altitudes and distances of which aeroplanes were capable. From the earliest days, a crossing of the North Atlantic by air had been a cherished ambition, and only the outbreak of war in 1914 prevented competition during that year for the Daily Mail prize of 10,000 pounds offered in 1913 to the first aviators to accomplish a direct (i.e. nonstop) crossing. As recorded elsewhere in the series, the prize was ultimately won in June by

John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown

for their flight in a modified Vickers Vimy, but in the month preceding this, another Atlantic crossing, with stops en route, had been made by an American flying-boat, the NC-4. That this aircraft should have been of Curtiss manufacture was particularly appropriate, for Glenn Curtiss was a pioneer of seaplane design and his company's flying-boat America, was designed originally as a 1914 contestant in the transatlantic competition.

The NC-4 was one of four NC (Navy-Curtiss) flying-boats, built during World War I originally to provide patrol cover for American shipping in the Atlantic against the attentions of German U-boats. The requirement was drawn up, and the aircraft was designed by the Navy in September 1917. It featured a short 45 ft. (13.72 m) length hull of advanced hydrodynamic design, and was intended to be powered by three engines. The first four aircraft were numbered separately NC-1 to NC-4, but the war was ending even as flight testing began. The NC-1 (three 400 hp Liberty engines) flew for the first time on October 4,1918, and on November 25 gave striking proof of its load-lifting abilities by carrying 51 people on a single flight -- a world record. Nevertheless, the three-engined installation was considered inadequate for transatlantic flying, and completion of the second, third and fourth aircraft was delayed while a fourth engine was included in the design. First flights were made on April 12 (NC-2), April 23 (NC-3) and April 30 (NC-4), NC-2 having been modified with its engine mounted as tandem pairs was found to be an unsatisfactory configuration, while the other two aircraft retained the between-wings separate tractor layout of three engines and had the fourth mounted, as a pusher, at the rear of the hull. It was decided to enter the Navy-Curtiss machines for the transatlantic attempt, for which they were redesignated NC-TA. On March 27th, the NC-1's right wing had sustained storm damage, and was given the wing from NC-2. The NC-2 whose engine layout had proved unsatisfactory was again cannibalized to supply parts for the NC-1, when its left wing was damaged by fire on May 5th, in a hangar at Rockaway, New York. |

| The Journey Begins |

|

On Thursday morning, May 8th, NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4 took off from Rockaway for Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the first leg of the transatlantic journey. The flight was under the command of John Towers, who was also commanding officer and navigator of NC-3. NC-4 was commanded by Lieutenant Commander Albert C. Read, and NC-1 by Lieutenant Commander Patrick N. L. Bellinger.

Offshore of Cape Cod, NC-4's center engine failed—she landed at sea and taxied to the Naval Air Station at Chatham, Massachusetts, for repairs. NC-3 and NC-1 arrived at Halifax without incident, but next morning serious cracks were discovered in their propellers, and a day was lost replacing them. |

|

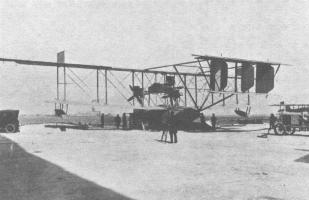

The NC-2 in its original configuration. The third engine mounted as a pusher on the center nacelle. It was later modified with tandem engine pairs and found to be an unsatisfactory configuration. |

|---|

|

On the 10th, NC-1, and NC-3 continued their flight to Trepassey, Newfoundland, the jumping-off place for their spanning of the Atlantic.

At Trepassey, a small fleet had gathered to support the transoceanic flight. When the NCs took off across the Atlantic, twenty-one destroyers would be on station at 50-mile intervals between Cape Race, Newfoundland, and Corvo, the westernmost island of the Azores. The destroyers were to serve as visual and radio navigation aids and communication links. They were also to provide weather intelligence, and if necessary, rescue service. The security of having twenty-one destroyers strung out between Newfoundland and the Azores may give the impression that the flight was a very simple affair. But in 1919, when aerial navigation across a great trackless sea was not yet an art, much less a science, when aircraft radio was primitive and unreliable, and when many flight instruments had yet to be invented, it was not easy to zero in on nine tiny islands scattered over several hundred square miles of ocean. If an eastbound pilot missed the Azores, his next landfall was Africa, hundreds of miles away. Repairs were completed on NC-4, but she was kept at her Chatham mooring by gale-force winds and rain. There was concern among NC-4's crew that, if Commander Towers received a favorable weather forecast, he would feel obliged to take advantage of it and "go" for the Azores without them. Newspapers were calling NC-4 the "lame duck" and circulating ill-founded rumors that she would be withdrawn from the flight. The weather cleared on the 14th, however; NC-4 flew to Halifax and arrived at Trepassey the next day. Towers had received a favorable weather report on the 15th and decided to go—without NC-4. But NC-3 and NC-1 proved to be overloaded with fuel and could not get off the water. The forecast for the 16th was even better, and none had wanted to leave NC-4 behind—now all three could go together. On Friday evening, May 16, the three NC boats roared in turn down Trepassey harbor and flew off into the gathering darkness over the Atlantic. The evening takeoff was necessary so that they could reach the Azores after sunrise next day and enjoy daylight landing conditions. |

|

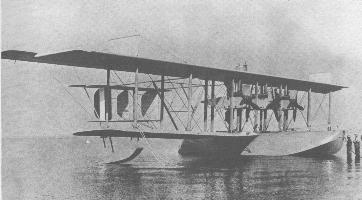

The NC-1 in its original configuration, with the pilot and copilot in the main hull. Later to conform to the NC-3 and NC-4, the crew was shifted to a cockpit located in the center nacelle. |

|---|

|

The night passed without incident. The fliers flew over the destroyers on their ocean stations with reassuring regularity. During the night the three planes broke from their flight formation to avoid the risk of collision. Furthermore, each airplane had its own flying characteristics and cruising speed—NC-4 was the fastest and NC-1 the slowest of the three.

Troubles came with the dawn, and sunrise was closely followed by the onset of fog. In NC-3, Towers spotted a ship on the foggy horizon that he took to be one of the station destroyers and altered course accordingly. It proved to be the cruiser Marblehead returning from Europe, and this misidentification produced an erroneous bearing that took NC-3 far off course. Finally, with fuel running low, and determining by dead reckoning that he was somewhere close to the Azores, Towers decided to put down long enough to obtain a navigation sight. The seas were running high and the landing was so rough that the impact collapsed the struts supporting the centerline engines. In this condition, NC-3 would go no farther—except as a surface craft. Bellinger was having similar difficulty, but landed NC-1 without accident. Once down however, she could not get off again through the 12-foot high waves that were running, and would indeed be lucky to survive them. Read, in NC-4, had also "run out of ships" and was virtually lost in the fog, which one time was so thick that the crew could not see from one end of the plane to the other. The pilot became totally disoriented and almost put the big plane into a spin. Ensign Herbert Rodd, the radio officer was successful however, in picking up radio bearings and weather information from the destroyers hidden below by fog and clouds. After more than 15 hours in the air, Read's dead reckoning and Rodd's radio reports gave assurance that NC-4 was very near the Azores. A sharp lookout was kept by all hands. Suddenly island greenery appeared through a small break in the fog. It was Flores, one of the western Azores. With Flores as a checkpoint, Read swung NC-4 eastward for the islands of Fayal and Sao Miguel. The fog began to thin, but soon thickened again, and Read settled for immediate haven on Fayal. NC-4 landed in the harbor of Horta a bit before noon. Within minutes a great bank of fog blotted out the port completely. Upon boarding the cruiser Columbia, base ship for the NCs at Horta, the first thought of Read and his men was to ask about NC-3 and NC-1. It was soon apparent that NC-1, trapped and pummeled by the great waves, was lucky to stay afloat let alone take off. The Greek freighter Ionia appeared out of the fog and rescued Bellinger and his crew. Attempts to salvage the derelict NC-1 were thwarted by the heavy seas and she finally sank three days later. |

|

|---|

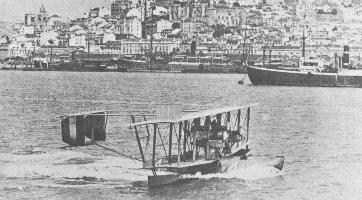

| The NC-4 triumphantly arrives in Lisbon, Portugal May 28, 1919. |

|

The fate of NC-3, after remaining a mystery for 48 hours, proved to be a saga of the sea. Before leaving Trepassey, Towers had jettisoned the emergency radio transmitter to reduce weight for takeoff. Thus NC-3 could receive radio calls but was "voiceless," and pure seamanship had to take over. Towers figured that within two or three days the NC-3 would drift in close to the island of Sao Miguel in the eastern Azores. His estimates were proved correct on Monday afternoon, May 19th, when NC-3, battered and almost derelict, sailed into the harbor of Ponta Delgada.

For almost three days NC-4 rode her moorings at Horta, kept there by high seas, rain, and fog. On the 20th, the weather cleared enough to permit takeoff, and in less than two hours she reached Ponta Delgada. Read planned to take off for Lisbon the next day, but weather and engine troubles delayed the departure for a week. The men of NC-4 were up before dawn on Tuesday, May 27th. Lieutenant James L. Breese and Chief Machinist's Mate Eugene S. Rhoads diligently pampered the plane's engines. Herbert Rodd bestowed equal care on his indispensable radio set to ensure that it was ready to go. At word from Read, Lieutenant Elmer Stone advanced the throttles and sent the big flying boat charging down the harbor in a great V-shaped wedge of spray, lifting off at 08:18 hours. Another chain of destroyers extended between the Azores and Lisbon. As NC-4 over flew them, each ship radioed her passage to the base ship Melville at Ponta Delgada and the cruiser Rochester in Lisbon, who in turn reported to the Navy Department in Washington. Finally word came from the destroyer McDougal, last ship in the picket line, that completion of the flight was only minutes away. In NC-4 all eyes peered eastward where the horizon was fading into the deep purple of twilight. Then at 19:39 hours, from the center of that darkening line, there flashed a diamond spark of light—Cabo da Roca lighthouse—and the westernmost point in Europe had been sighted. Minutes later NC-4 roared over the rocky coastline and turned southward toward the Tagus estuary and Lisbon. According to Read, a man of few words, this moment was "perhaps the biggest thrill of the whole trip." Each man on board realized that "No matter what happened—even if we crashed on landing—the transatlantic flight, the first one in the history of the world, was an accomplished fact." At 20:01 hours on May 27,1919, NC-4's keel sliced into the waters of the Tagus. The first transatlantic flight was indeed an accomplished fact. After two days in Lisbon, where all three NC crews were generously feted by the Portuguese government and the city of Lisbon, NC-4 continued her flight to Plymouth, England, to the port whence the Pilgrim Fathers had left for America 299 years before. On the morning of May 29th, she departed Lisbon, but a few hours later off Monedego River, she was forced down by engine trouble. This was soon repaired, but the day was spent and Read refused to risk a landing at Plymouth in darkness. So NC-4 flew only to El Ferrol, Spain, for the night. The next day NC-4 made the final leg of her flight. NC-4 landed in Plymouth harbor early in the afternoon of May 31st, after being escorted into the harbor there by three Felixstowe F.2A flying-boats of the Royal Air Force. During the twenty-four days of this transatlantic flight, it invariably held the front page banner space of American newspapers. But other remarkable Atlantic flights followed, and the world soon forgot the triumph of NC-4 and the skill and sagacity of her crew. After May 1919, the world knew that men would fly the Atlantic again—and again and again. They would fly it faster and with fewer stops. They would fly it nonstop, in company, and alone. They would fly it with tens and even hundreds of passengers, at speeds and with comforts difficult to imagine in 1919. But no one again could be first. That honor belongs to Lieutenant Commander Albert C. Read, his crew of five, and the United States Navy's NC-4. The NC-4 made a triumphal return to the USA later, ending a celebratory tour of the eastern and southern seaboard by flying up the Mississippi to St. Louis. Here it was handed over to the Smithsonian Institution. Later it was given to the Naval Air Museum in Pensacola, Florida and is currently on display. After the Armistice the Naval Aircraft Factory at Philadelphia built six more NC-type flying-boats. These were built initially as tri-motors, but four were later converted to an NC-4-type four-engined layout, the other two meanwhile having been lost. The converted aircraft served during 1920-22 with the US Navy's East Coast Squadron before being retired. |

Chronology of Events |

|

May 8,1919 - NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4 Take off from Jamaica Bay at

Far Rockaway, Queens for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Enroute the NC-4

develops engine trouble off Cape Cod and diverts to Chatham

Massachusetts. The NC-1, NC-3 arrive at Halifax without incident.

May 10,1919 - NC-1, NC-3, continue to Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland. May 14,1919 - NC-4, flies to Halifax and arrives at Trepassey Bay the next day. May 16,1919 - NC-1, NC-3, and NC-4 leave Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, for Horta, Azores Island. May 17,1919 - NC-4 arrives at Horta, Azores Island. NC-1 lands at sea and sinks 3 days later. Its crew is picked up the Greek freighter, Ionia . NC-3 is badly damaged after landing off Horta. May 19,1919 - NC-3 battered and almost derelict, sailed into the harbor of Ponta Delgada. May 27,1919 - NC-4 leaves Horta and arrives at Lisbon, completing the first American transatlantic flight. May 29,1919 - NC-4 leaves Lisbon for Plymouth and diverts to El Ferrol, Spain due to engine trouble. May 31,1919 - NC-4 arrives at Plymouth, England. |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Navy-Curtiss NC-4 Flying Boat | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 126 ft 0 in (38.40 m) |

| Length: | 68 ft 3 in (20.80 m) |

| Height: | 24 ft 4 in (7.40 m) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 16,000 lb (7,257 kg) |

| Operational: | 27,386 lb (12,422 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 91 mph (146 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 4,500 ft (1,372 m) |

| Range: | 1,470 miles (2,366 km) |

| Endurance: | 14.8 hours @ cruise |

| Powerplant: | |

| Four Liberty 400 hp 12-cylinder Vee type. | |

|

Additional Comments from First Across Home Page |

|

1. Lt. Stone is often forgotten by Navy buffs as a Coast Guardsman. He

was Coast Guard Aviator #1.

2. The Naval Reservists (USNRF) were often slighted by not mentioning their Reserve status (this means they did NOT go to the Naval Academy, but WERE on active duty all the same; i.e., regular college graduates or commissioned from the ranks). 3. Eugene Rhoads was a Chief Machinist's Mate (Air) as opposed to a surface navy (ship) machinist. They were sometimes called MECHANICIAN (a French term) in those days. Chief Petty Officers feel slighted if the "Chief" is left off. Rhoads' name is often misspelled even in contemporary accounts. RHOADS is correct. |

© The Aviation History On-Line Museum. 2007 All rights reserved.

Update July 31,2007.