|

At the south end of Lake Keuka, one of New York State’s Finger Lakes, sits the small village of Hammondsport. Settlers moved into the area by the 1790s, in 1829 Lazarus Hammond surveyed the area, and the village itself was incorporated in 1856. The village has long been one of many engaged in New York’s profitable wine-growing industry. These days, the village boasts a population of only a few hundred people. However, the village also can boast that—on May 21st, 1878—it was the birthplace of one of aviation’s greatest pioneers, Glenn Hammond Curtiss.

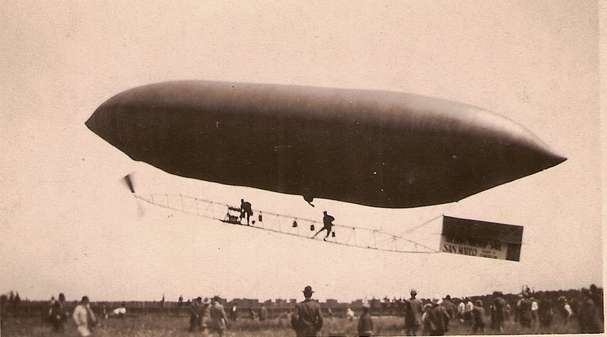

Curtiss’s father, Frank, ran a harness business, but died when his son was only four years old. Curtiss’s mother, Lua Andrews Curtiss, was left to raise young Glenn and his younger sister, Rutha. At age 6, Rutha came down with meningitis, which quickly caused her to become deaf. Lua Curtiss moved her small family to Rochester, New York, so Rutha could attend the Western New York Institute for Deaf-Mutes, now known as the Rochester School for the Deaf. (According to archivist Nancy McCrave of the Rochester school, Rutha attended from September 1889 to June 1903.) To provide for the family, Lua attended the state teacher’s college in Geneseo and ran a storefront school in Rochester. Despite Curtiss’s obvious intelligence, his formal education ended at the end of 8th grade. To help with the family finances, he went to work for the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company, now known as the Eastman Kodak Company. Later, he took a messenger’s job with Western Union. In March, 1898, Curtiss married Lena Pearl Neff and settled in Hammondsport. On their wedding day, Curtiss was only 19 and Lena was only 17. Despite their youth, they had very similar personalities, which created a strong and stable marriage. Like those other aviation pioneers, the Wright Brothers, Curtiss as a youth had an interest in bicycles, and developed a business designing, building, and repairing the vehicles. His business grew so much that he also opened stores in Bath and Corning, New York. Unlike the Wright Brothers, however, Curtiss was more willing to risk the dangers associated with speed. He started adding motors to his vehicles, converting them to motorcycles. In 1901, tragedy struck the Curtiss family. They had a boy that they named Carlton, but he lived for only 11 months. To handle her grief, Lena threw herself into the family business. And for the rest of their marriage, she continued to work closely with her husband. Curtiss not only made and sold bicycles, but also started racing them. In 1903, on Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day), Curtiss used a V-twin motorcycle to win a hill climb, win a ten-mile race, and set a new one-mile speed record. As one of the leading motor builders in America, Curtiss eventually received the attention of the balloonist Thomas Scott Baldwin. In 1904, Baldwin flew his airship—the California Arrow—at the St. Louis World’s Fair. The ship was powered by a Curtiss engine. After the fair, Baldwin tried to interest Curtiss in not only building engines, but also working in the budding field of aviation. At first, Curtiss was reluctant to participate. However, the two men grew close, and Baldwin moved to Hammondsport and started building balloons and dirigibles in town. | ||

| The California Arrow was powered by a Curtiss engine. |

|

|

Knowing of the Wright Brothers' success with airplanes, Curtiss wrote to the brothers in May, 1906, to see if they might have an interest in buying one of his engines. He also met them in August, but the fiercely independent Wrights still had no interest in making a purchase.

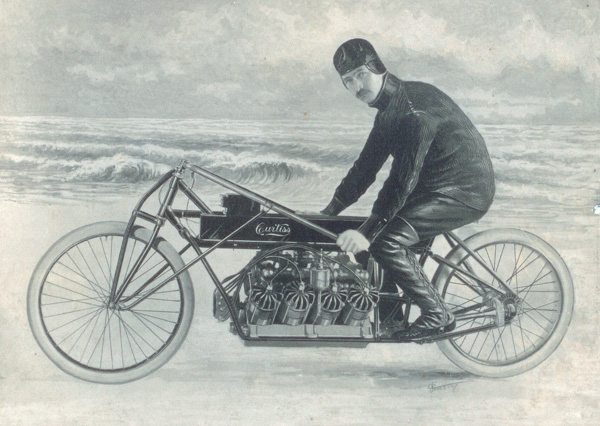

Although Curtiss failed to win over the Wrights, at this time another inventor succeeded in making aviation history. For a few years, the Brazilian-born balloonist Alberto Santos-Dumont had been experimenting in France with heavier-than-air flight. After testing various designs, he eventually built and flew an airplane called the Quatorze-Bis, which was designed like a large box kite. For a November flight of over 700 feet, he won the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first public, heavier-than-air, powered flight in Europe. Back in the United States, the next year, 1907, was a very busy time for Curtiss. In January, for example, he rode the world’s first V-8 motorcycle to a speed of 136 miles per hour in Ormond Beach, Florida. Having driven the cycle faster than even the typical locomotive of the day, he became known as “the fastest man on earth.” In June, he flew over Hammondsport in a Thomas Baldwin dirigible powered by a Curtiss engine. This was the very first time that Curtiss went aloft in any sort of aircraft. After alighting from the craft, he was now so interested in human flight that he soon started planning how to make the dirigible fly faster. | ||

| Glenn Curtiss rode the world’s first V-8 motorcycle to a speed of 136 mph and became known as “the fastest man on earth.” |

|

| In October, he joined the Aerial Experiment Association, or AEA, a group founded by Alexander Graham Bell, the famous inventor, and financed by Bells’ wife Mabel who—like Curtiss’s sister Rutha—was deaf. In December, Curtiss wrote again to the Wright Brothers, offering them a free engine for aviation use, but they again refused his offer. | ||

| The Red Wing was designed in collaboration with Lt. Thomas J. Selfridge. In this photo, Casey Baldwin is at the controls. |

|

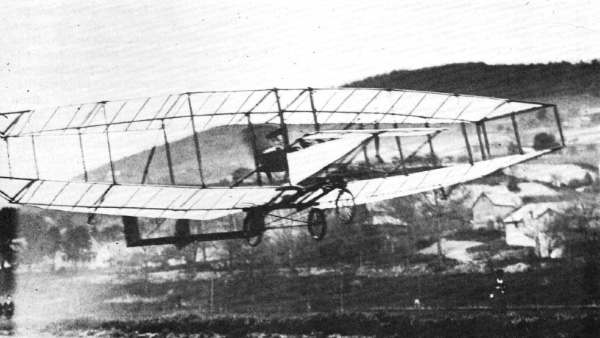

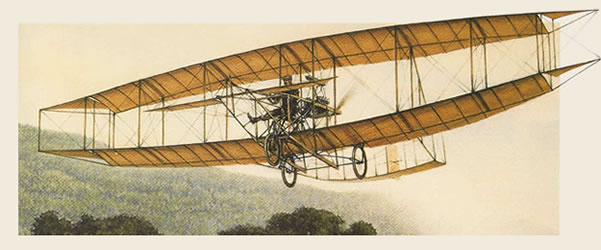

| Nineteen-hundred-and-eight also was a busy year for Curtiss, as he worked closely with Bell’s organization. Besides Bell and Curtiss, the group’s leaders included the Canadians F. W. “Casey” Baldwin and John McCurdy, and a U.S. Army Lieutenant, Thomas Selfridge. On March 12, “Casey” Baldwin took off from the frozen surface of Keuka Lake in an airplane called the Red Wing, and flew nearly 319 feet in 20 seconds. On its second flight, the plane hit the frozen lake on one wing and crashed. Two months later, Curtiss made a controlled flight of over 1,000 feet in an aircraft called the White Wing. This was the first American aircraft to use ailerons for control purposes. | ||

| The White Wing was designed by F. W. Baldwin and powered by a Curtiss engine. |

|

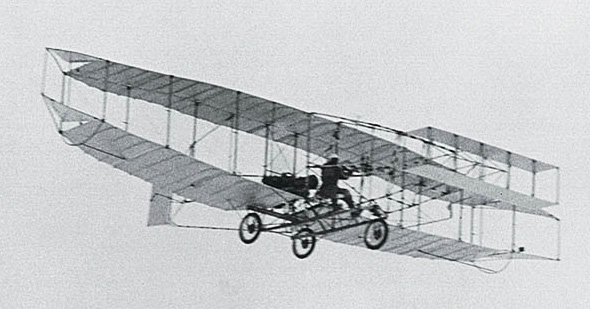

| And, on July 4, Curtiss flew a plane called the June Bug across Pleasant Valley in Hammondsport a distance of 5,090 feet. For this feat, he won the first leg of the Scientific American trophy, which required an unassisted take-off and straight flight of at least one kilometer. With these flights, the AEA became the first group in North America besides the Wrights to design, build, and fly airplanes. | ||

| The June Bug was designed by Glenn Curtiss and powered by a Curtiss engine. |

|

| By November, Curtiss and John McCurdy had added floats to the June Bug aircraft and renamed it the Loon. The AEA tried often to lift the plane off the waters of Lake Keuka, but had no success. McCurdy eventually damaged a float on the plane, and the aircraft sank at the dock. | ||

| The Loon. |

|

| Despite failing to fly an amphibious craft, the group had success with a new land-based airplane, the Silver Dart. This plane had larger control surfaces, which increased its maneuverability over the group’s previous machines. After trials at Hammondsport, the AEA took the Silver Dart to Bell’s Canadian home in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. In February, 1909, McCurdy flew the Silver Dart into the air, making the first successful airplane flight in Canada. | ||

| The Silver Dart was designed by J. A, McCurdy. Augustus Herring, an associate of Octave Chanute, assisted in the construction. |

|

|

Nevertheless, in March, the AEA disbanded and bequeathed its aircraft designs and patents to Curtiss. Curtiss historian Kirk W. House has summarized the legacy of the AEA’s members as follows: “They had built four increasingly sophisticated flying machines, along with a hang glider and a giant kite. They had heightened interest in aviation in the United States and Canada, and contributed to the birth of military air power. In the process, they had pioneered or advanced several key aeronautical innovations, including ailerons, tricycle landing gear, and the liquid-cooled aero engine.”

Bell, McCurdy, and Baldwin built a few more planes at Baddeck, but Curtiss himself now was back on his own. His next plane was called the Gold Bug—or Curtiss No. 1—which he sold to the New York Aero Club for $5,000. The club renamed the aircraft the Golden Flyer. Trying to avoid a patent battle with the Wrights, Curtiss had designed the airplane with new control surfaces. In July 1909, he successfully flew the plane in a circular course. However, both the new plane and its sale to the Aero Club further angered the Wrights, who began a long patent war with Curtiss in August. Also in August, the city of Reims, France, held the world’s first international aviation meet. Curtiss attended the event, along with other aviation pioneers such as Louis Bleriot, the first person to fly the English Channel, and Louis Paulhan, pilot of the world’s first successful seaplane. The Wright Brothers, who were selling their own aircraft in Germany at the time, did not attend the meet. In Reims, Curtiss flew another plane, the Reims Racer—or Curtiss No. 2—to a record speed of almost 47 miles per hour, earning himself the Gordon Bennett Cup, a speed trophy sponsored by James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the New York Herald. On September 21st, Curtiss arrived in New York City from France to participate in the Hudson-Fulton Celebration. This city-wide event sought to honor the centennial of Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat and the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s arrival in New York harbor in his 85-foot ship, the Half Moon. Curtiss traveled up to Hammondsport, but returned to New York on September 29th with an airplane that had just a four-cylinder engine. The next day, Curtiss’s underpowered plane made a short and unimpressive flight in a strong wind. That same day, Wilbur Wright did impress New Yorkers with a two-mile flight around Governor’s Island, at the southern tip of Manhattan. That afternoon, he also took off from Governor’s Island, flew past the Statue of Liberty, banked sharply, and returned to base. Because of contractual obligations in St. Louis, Curtiss did no more flying in New York City that season. With Curtiss grounded, Wilbur Wright wowed New Yorkers once again. On October 4th, Wright took off from Governor’s Island, flew ten miles up the Hudson River to Grant’s Tomb, and then returned to base. His 20-mile flight lasted over 33 minutes, averaging 36 miles per hour. An estimated one million New Yorkers witnessed at least some part of his flight. On May, 29th, 1910, Curtiss had much more success in impressing New Yorkers. He took off from Albany in a new plane, the Hudson Flyer, and headed south for New York City. This plane, with a 50-horsepower, 8-cylinder engine, was up to its task. Curtiss made a planned landing near Poughkeepsie, New York, another stop at the north end of Manhattan Island, and then landed at Governor’s Island. The flight of 151 miles took 2 hours, 51 minutes, and averaged 52 miles per hour. It was the longest airplane flight to date, and won for Curtiss both a $10,000 prize and permanent possession of the Scientific American trophy. Despite the crude design of early airplanes, both the Wright and Curtiss machines seemed to reflect their inventors’ distinct personalities. The Wrights’ machines looked simple and unadorned, their wings were ramrod straight and precisely aligned, and wires and joints looked tightly assembled. In contrast, Curtiss’s machines seemed to reflect their designer’s daredevil, motorcycle-riding past. Wings had jaunty curves, one plane mixed planed wood with bamboo, and wires seemed to criss-cross every which way between airfoils. By the 1910s, however, Curtiss started to pull away from the Wright Brothers with both the innovativeness and quantity of his airplanes. Admittedly, part of Curtiss’s emerging dominance had nothing to do with his own efforts. After all, Wilbur Wright died in 1912, and Orville sold his aircraft corporation to a syndicate of investors in 1915. Nevertheless, with his innovative spirit, Curtiss advanced the science and technology of human flight far beyond what the Wrights finally accomplished. As an innovator, Curtiss began to think and act seriously about naval aviation. In May and June of 1910, he tried a second time to fly an airplane off the surface of Keuka Lake, but had no success. In November, at Hampton Roads, Virginia, Eugene Ely, one of Curtiss’s exhibition flyers, successfully took off in a land-based Curtiss aircraft from a specially designed platform on the U.S. Navy’s scout cruiser Birmingham and then flew the plane to shore. In December, Curtiss arrived at North Island in San Diego Bay to start a U.S. Navy aviation school. In mid-January, 1911, Ely rounded off the feat that he had begun the previous November. He took off in a land-based Curtiss airplane from the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno, California. Then, with his wife Mabel looking on and holding a camera, he landed on a specially-built platform on the U.S. Navy cruiser Pennsylvania in San Francisco harbor. This event marked the first time that an aircraft made a ship-borne landing. A few days later, at North Island, Curtiss himself made his first successful takeoff from water. And a few days after that, he also made the first successful hydroplane flight to a ship. In response to the achievements of Curtiss and his fellow pilot, in May the U.S. Navy ordered two Curtiss A-1 hydroplanes. These achievements also earned him the title of “Father of American Naval Aviation.” Curtiss became an actual father has well. In 1912, his wife gave birth to a second child, Glenn Curtiss, Jr. Anticipating the responsibilities of fatherhood, Curtiss already had given up exhibition flying. A year later, he visited the airplane factory of Thomas Sopwith in England, who was building tractor airplanes. Unlike the earliest airplanes, with propellers in the back that pushed planes forward, tractor aircraft have propellers up front, like most contemporary aircraft. Sopwith’s designs, plus the U.S. Army’s interest in tractor training aircraft, put Curtiss into high gear as an airplane builder. His first major tractor airplanes were the JN-1 and JN-2. He followed those models with the JN-3, of which he built fewer than 100. In 1916, Curtiss modified the JN-3 to improve its performance and named the new model the JN-4, nicknamed the Jenny. Over the next few years, he came out with over fifteen versions of this plane and manufactured more aircraft than any other American during World War I. In 1914, Curtiss once again incurred the ire of the Wright family. In an attempt to prove that Samuel P. Langley had invented the first machine capable of sustained flight, the Smithsonian Institution contracted with Curtiss to verify if Langley’s 1903 Aerodrome could fly. The Smithsonian shipped Langley’s machine to Hammondsport, where Curtiss and his associates modified it and eventually flew it off of Lake Keuka on May 28 and June 2. The Smithsonian’s witness for these flights, Dr. Albert Zahm, later concluded that the Aerodrome “has demonstrated that with its original structure and power, it is capable of flying with a pilot and several hundred pounds of useful load. It is the first aeroplane in the history of the world of which this can truthfully be said.” However, another witness of these flights was Orville Wright's older brother Lorin. He compiled a long list of Curtiss’s modifications that, to the Wrights, verified that the plane could not have flown without those changes. In light of the competing claims, Orville Wright and the Smithsonian argued for three decades over who had first invented a flyable plane. By 1943, the two parties had reached an agreement in favor of the Wrights, and the Wright Flyer of 1903 now hangs proudly in the Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC—recognized as the world’s first “powered heavier-than-air flying machine.” Curtiss’s leadership as a manufacturer also was aided by another development. To help meet the war’s aviation needs, the U.S. government pressured the Wright and Curtiss companies to resolve their patent differences. Both companies received cash settlements for resolving their disputes. The Wright family’s patent war with Curtiss finally ended. When it comes to crossing the Atlantic, many people may think that Charles Lindbergh was the first to do so in 1927. As marvelous as his achievement was, he was just the first person to fly solo from New York to Paris. Back in 1919, Curtiss flying boats manned by U.S. Navy aviators set out to become the first to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. On May 8, three flying boats took off from Naval Air Station Rockaway, NY. The three planes flew on to Nova Scotia and then to Newfoundland. On May 16, they all left Trepassey Bay and headed for the Azores off the coast of Portugal. Two of the three planes could not complete the overall trip. However, on May 17th, flying boat NC-4 reached Horta in the Azores. Ten days later, it flew successfully to Lisbon, Portugal. Finally, on May 29th, the plane left Lisbon, and eventually reached Plymouth, England on May 31st. The naval aviators quickly became famous and returned home to the United States as national heroes. To honor the flyers, Curtiss hosted a banquet for them on July 10th at New York’s Commodore Hotel. According to Curtiss’s biographer C.R. Roseberry, the dining room looked like the cabin of a huge seaplane. The evening was hosted by American humorist Irvin S. Cobb. Stage entertainment included actors posing as Christopher Columbus and Neptune, mythic king of the ocean. To promote naval aviation, the NC-4 later flew down Atlantic seaboard, around Florida, and then up the Mississippi River to the Great Lakes. Despite the magnificent achievement of his flying boats, Curtiss decided to reduce his involvement in the aviation industry. He sold his controlling interest in the corporation that bore his name, started spending time in Florida, and bought major tracts of land. But his interest in innovation and invention did not fade under the heat of the Florida sun. Roughly ten miles northwest of downtown Miami, he helped establish the cities of Hialeah, Miami Springs, and Opa-Locka. He built an airport in Opa-Locka and an Arabian-style hotel in Miami Springs. He also built his family a Pueblo-style house in Miami Springs and took frequent hunting trips in Florida’s everglades. Another Curtiss invention was the Adams Motor Bungalo, named for his business partner and half-brother, G. Carl Adams. This bungalo was one of the forerunners of the modern RV trailer. In 1929, the Curtiss-Wright Corporation took shape from twelve Wright and Curtiss affiliated companies, and became the second-largest firm in America. The Curtiss-Wright Corporation still exists today. The company’s official website describes it as “a diversified global provider of highly engineered products and services of motion control, flow control, and metal treatment.” In the rough economic market of late 2008, the firm still reported assets of over two billion dollars and a net income of over 109 million dollars. Kirk House has described Curtiss’s Florida legacy as follows, “Curtiss founded 18 corporations in Florida, served on civic commissions, donated extensive land and water rights, and vigorously promoted the growth of the Miami region.” Just 52 years old, Curtiss was poised to continue his life of innovation and invention. Unfortunately, in early July, 1930, he was battling a lawsuit brought by August Herring, a former business partner. On his way to court in Rochester, New York, Curtiss doubled over in pain because of an attack of appendicitis. Herring’s lawyers accused Curtiss of faking his illness, but Curtiss was rushed to Buffalo General Hospital, where he underwent what appeared to be successful surgery. On the evening of July 22, Curtiss felt well enough to give dictation as part of his legal defense in the Herring lawsuit. Nevertheless, on the morning of July 23, his private nurse found him dead on the floor of his hospital room. He is buried in the family plot in Pleasant Valley Cemetery, not far from where he took off in 1908 in his June Bug aircraft to make aviation history. Despite having lived in Florida for ten years, Glenn Hammond Curtiss was still a son of Hammondsport, New York. His funeral service was held at St. James Episcopal Church in the small village where he was born. Note: We wish to thank the aviation historians Von Hardesty and Kirk W. House for reviewing this essay for accuracy. Any errors are ours alone. | ||

|

David Langley is a freelance writer who resides in New York. |

Return to Early Index

© The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

All rights reserved.

November 18, 2009.