|

In 1861, the Wrights’ first child, Reuchlin, was born in a log cabin near Fairmont, Indiana. He was—over the years—a teacher, lumberyard clerk, bookkeeper, railroad man, and farmer. The Wrights’ second child, Lorin, was born in 1862. Early in his career, he worked as a bookkeeper, but eventually became a city commissioner in the Wrights’ hometown of Dayton, Ohio.

The third child, Wilbur, was born on a farm near New Castle, Indiana in 1867. He attended Richmond High School in the same state, but never actually graduated from there because he never applied for his diploma. He wanted to attend Yale University, but his mother’s severe illness prevented him from doing so. In June, 1869, the Wright family moved to Dayton, Ohio. The Wright’s fourth surviving child was Orville, born in 1871. He grew up in Dayton and attended Central High School, where his grades were good, but not great. One of Orville’s classmates was the African-American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar, who was the only black student in the class. | ||

| The Wright home at 7 Hawthorn Street, Dayton, Ohio. |

|

|

The Wrights’ last child and only surviving daughter, Katharine, was born in 1874. After attending the Dayton public schools, she attended Oberlin College, where she majored in Greek and Latin. She was—in fact—the only Wright sibling to graduate college. As a young professional woman, she taught classical literature at Steele High School in Dayton.

In 1877, Milton was elected a bishop in his denomination. A year later, he started traveling the Midwest and Plains states on business for the church. Seven years later, he resettled in Dayton for the rest of his life. Their father was is credited with providing Wilbur and Orville with their original inspiration in flight. A toy helicopter, of the type that was designed by Alphonse Pénaud, was given to the boys at an early age. It made such an impression, that it inspired them to develop their own airplane that would someday carry a man in flight. At age 15, Orville and a hometown friend named Edwin Sines published a newspaper called The Midget, which lasted only one issue. However, by 1889, Orville and his older brother Wilbur were running their own printing business, Wright and Wright Job Printers. During that year, they published a newspaper called the West Side News, which they later renamed The Evening Item, but the paper lasted only a few months. That same year, Susan Wright died from tuberculosis at age 58. |

| In 1891, a man named Otto Lilienthal—living in Berlin, Germany—made his first successful glider flight. Like many early aviators, Lilienthal thought that successful flying devices had to take the shape of birds, whose wing structures he had studied carefully. During his career, he made about 2,500 flights in his bird-shaped gliders. |

|

| Otto Lilienthal. |

|

A year later, in 1892, the Wright Brothers became interested in bicycles when the cycling craze was sweeping the country. The two brothers had inherited their mother’s practicality and inventiveness, and over a few years the developed some sturdy bicycle designs of their own. They opened a bicycle shop called the Wright Cycle Exchange and eventually renamed it the Wright Cycle Company, which had six different locations until it closed in 1916.

In August 1896, Orville contracted typhoid fever and was seriously ill for several months. However, in the same year, Wilbur and Orville began developing an interest in aviation, inspired by the work of three key men. | |

| • The first was Otto Lilienthal himself, the German who had experimented with gliders in a field just outside of Berlin, and whose death in a recent gliding accident spurred the brothers’ curiosity about the possibility of powered, heavier-than-air flight. | • The second was the French-born Octave Chanute, who came to America, eventually moved to Chicago, and became the foremost American engineer of his day. As a bridge builder, Chanute encouraged the Wrights, through letters, to abandon the idea of bird-shaped wings in favor of a stronger, double-wing design. | • The third man was Samuel P. Langley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and a key source of aviation data at the turn of the century. |

|

By 1899, Wilbur had begun thinking seriously about how to advance the science of human flight. On May 30th of that year, he wrote to the Smithsonian, looking for aviation publications. More specifically, he wrote, "I am about to begin a systematic study of the subject in preparation for practical work to which I expect to devote what time I can spare from my regular business." He continued, "I wish to obtain such papers as the Smithsonian Institution has published on this subject, and if possible a list of other works in print in the English language." With the typical Wright family reserve, he added, "I am an enthusiast, but not a crank in the sense that I have some pet theories as to the proper construction of a flying machine." With modesty, he concluded, "I wish to avail myself of all that is already known and then, if possible, add my mite to help on the future workers who will attain final success."

Inspired by Octave Chanute’s suggestion that the brothers should find a constantly windy place for flight tests, Wilbur also wrote to the U.S. Weather Bureau at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, asking about weather conditions there. J. J. Dosher of the bureau replied that the Carolina beach was “about one mile wide, clear of trees or high hills.” This type of beach, Dosher said, would provide “many miles of a steady wind with a free sweep.” In 1900, the brothers made their first trip to Kill Devil Hill, North Carolina—near Kitty Hawk—and experimented with a glider-like kite attached to control cords. The brothers returned to North Carolina in July of 1901, and started testing a new glider at Kill Devil Hill. This gilder was larger than the 1900 version, and had a moveable front elevator. The glider performed worse than expected because it was based upon inaccurate data from Otto Lilienthal and John Smeaton about the lifting ability of various wing designs. | ||

| Wright Brothers 1901 Wind Tunnel on display in the Early Years Gallery at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. (U.S. Air Force photo) |

|

|

In light of this problem, in late 1901 the brothers reviewed their summer’s flight data and started testing differently shaped airfoils in a wind tunnel of their own design. The brothers completed a new glider with a greater aspect ratio in August of 1902, and they performed hundreds of successful glides at Kill Devil Hill during September and October. The 1902 glider—based on more accurate lifting tables and equipped with a moveable rudder—had more lift and better maneuverability than the brothers’ earlier gliders, convincing Wilbur and Orville that, in the next year, a motorized machine could make it into the air.

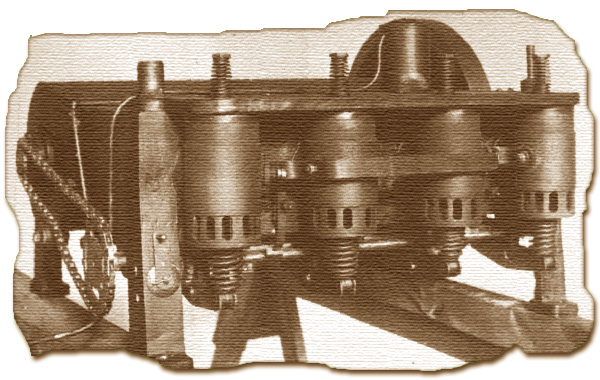

In February, 1903, the brothers’ mechanic, Charley Taylor, helped them to build and test a 12-horsepower motor to use in the airplane that would make history. Both the body and frame of the motor cracked during testing, so the threesome built a new unit made with an aluminum casting. | ||

| ||

| The Wrights, assisted by machinist Charles Taylor, designed and built their own engine. It weighed 200 pounds and produced just over 12 horsepower. | ||

|

In October of 1903, now back at their North Carolina beach camp, the brothers began assembling and testing their 1903 machine. On December 14th, Wilbur won a coin toss with Orville, so he was first to attempt to pilot the machine into the air. Unfortunately, Wilbur pulled up too sharply as he came off the launch rail, hit the sand, and damaged the front controls, which then needed repair.

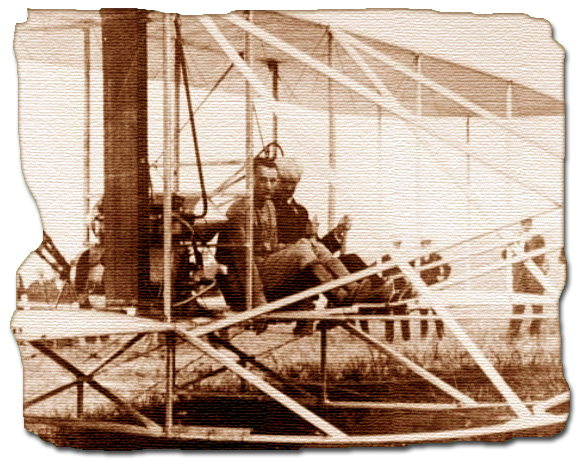

Three days later, on December 17th, Orville took his turn and made the first successful airplane flight in history, lasting just 12 seconds and covering 120 feet. Wilbur made a second flight, covering 175 feet, while Orville made a third covering 200. Wilbur made the fourth and final flight of the day, which lasted 59 seconds. The plane came to rest 852 feet from its lift-off point. The Wright flyer then suffered the fate of an earlier glider. A strong wind tumbled it over, damaging it beyond repair and preventing any more flights that season. Nevertheless, that evening Orville sent a telegram to his father, reporting the brothers’ flight results. The message read, “Success four flights Thursday morning – all against 21 mile wind - Started from level with engine power alone - Average speed through the air 31 miles – longest 57 seconds – inform press – Home Christmas.” The Wright family was proud of the two brothers. But in his diary, Bishop Wright grumbled about two newspapers that failed to appreciate the news he had shared with them. He wrote, “[the]Dayton Journal and Cincinnati Tribune contain nothing!” Now back at home from North Carolina, thinking of profits and ever protective of their invention, Wilbur and Orville applied for a patent for their flying machine. Their Petition to the U.S. Patent Office was just half a page long. | ||

| The 1905 Wright Flyer 3 taking off at Huffman Prairie. |

|

|

In 1904, instead of returning to North Carolina, the Wright brothers established a flying base at Huffman Prairie, a large, open field eight miles east of Dayton reachable by a commuter railroad line. In April and May of that year, the brothers started test flights with a new airplane, eventually accomplishing new feats. For example, on September 15th, Wilbur made the first half-circle turn ever in an airplane. And five days later, Orville made the first controlled circle, an achievement that Wilbur diagrammed for both their own records and for posterity.

Back in 1903, one Dayton newspaper had published a sketchy account of the brothers’ success at Kill Devil Hill. However, the first reliable, eyewitness account of the brothers’ flights appeared in 1905 in a journal called Gleanings in Bee Culture. The eyewitness—Amos I. Root from Medina, Ohio—traveled miles to verify rumors he had heard about flying machines and witnessed Orville’s first circle. Now assured of success, the Wright Brothers received for their flying machine Patent Number 821,393 from the U.S. Patent Office in 1906. Meanwhile, in France, another man—the Brazilian-born balloonist Alberto Santos-Dumont—was making aviation history. After the Wright brothers' flights in 1903, Santos-Dumont began to experiment with heavier-than-air flight. After testing various designs, he eventually built and flew an airplane called the Quatorze-Bis, designed like a large box kite. In October 1906, he won the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first public, heavier-than-air, powered flight in Europe. | ||

| ||

| Alberto Santos-Dumont's No. 14-bis made the first significant powered airplane flights in Europe. | ||

|

In that same year, the Wright brothers announced that they would no longer fly publicly until they could find a buyer for their airplane. A potential buyer soon appeared. In December 1907, the U.S. Army Signal Corps advertised for bids on a heavier-than-air flying machine. The brothers submitted a bid, and they had no real competition. Therefore, just two months later, in February 1908, they signed an Army contract for a machine costing 25,000 dollars. The requisition for the plane, based on a contract dated February 1st, ran just one page. On May 14th of that same year, the brothers carried a passenger, Charles Furnas of Dayton, on board an airplane for the first time in history.

By this time, other Americans also were learning how to fly. A group known as the Aerial Experiment Association, led by inventor Alexander Graham Bell, also was trying to get into the air. On July 4th, 1908, Glenn Curtiss of Hammondsport, New York, and part of Bell’s organization, flew his June Bug aircraft into the air, becoming the first American other than the Wrights to design, build, and fly an airplane. | ||

| ||

| The Glenn Curtiss June Bug. | ||

|

One month later, on August 8th in Le Mans, France, Wilbur held the brothers’ first formally announced public exhibition of their aircraft. Five weeks after that, on September 17th, Orville was performing aircraft trials for the Signal Corps at Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia. That day, he was badly injured when a propeller splintered in flight and sent his flyer crashing to earth. Doctors rushed to his aid as he lay stricken on the ground.

On board with him had been Army Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, who also suffered severe injuries. Selfridge died very soon after the crash, making him the first person ever to die in an airplane accident. In light of Selfridge’s death and Orville’s own injuries, the brothers suspended the Army trials until they could design more reliable propellers. | ||

| Lieutenant Thomas Selfridge, left, and Orville Wright at Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia, shortly before the ill-fated flight that led to the Lieutenant's death. |

|

|

In March of 1909, the brothers contracted with the Short Brothers of England to make six Wright flyers for European customers. In that same year, Wilbur was making triumphal flying displays in Europe. On July 17th and 18th, the City of Dayton held a homecoming celebration for the brothers, welcoming them home from Europe as heroes. The event was complete with a large welcoming committee; a parade with military units, marching bands, and floats; and the formal presentation of Congressional medals to the two brothers. On July 19th, the brothers escaped the uproar of Dayton to resume their Army trials, successfully completing them on July 30th. Therefore, on August 2nd, the U.S. Army agreed to purchase the Wright airplane.

Also in August, the brothers started a long patent war against Glenn Curtiss, a conflict that eventually made the brothers unpopular with other flyers and the press. Curtiss had built an airplane called the Golden Flyer, using a control system that the Wright Brothers believed infringed upon their patent. To capitalize on their legal case, the brothers incorporated the Wright Company on November 22, with Wilbur as president and Orville as one of two vice-presidents. In 1910 the Wright Company started a flight school at Huffman Prairie and another one in the warm-weather site of Montgomery, Alabama. The Ohio school closed in 1916, but the one in Alabama eventually became Maxwell Air Force Base. Both schools trained scores of aviators, but the unfortunate death of at least one student eventually convinced the brothers to give up the businesses. In late April 1912, Wilbur contracted typhoid fever while on a business trip to Boston, and fell seriously ill. Major newspapers, such as the New York Times, soon learned of his condition. Katharine telegraphed Orville in Washington, DC, telling him to ignore reports that his brother’s condition was serious. Nevertheless, on May 30th, after a month-long fight with his illness, Wilbur died at age 45. Reporting on his burial, a local newspaper praised him as “a spiritually minded man, remarkably free from covetousness, vanity, and pride.” Despite Wilbur’s death, Orville maintained his interest in making aviation progress. For example, in January 1913, he began testing an automatic stabilizer, the last invention that Wilbur and he had worked on together. Although the stabilizer worked well, the automatic gyroscope of inventor Elmer Sperry soon proved more effective for steadying aircraft. In February, 1913, Orville and Katharine left for Europe to visit business interests there. Just before the Dayton flood of March 25th to 27th, Orville and his sister returned to America. The flood greatly damaged the first floor of the Wright family home and bicycle shop. However, it did little damage to the glass photo negatives of the Wright’s early flights, the records of their experiments, and the remnants of the 1903 Flyer. In October of 1915, Orville sold the Wright Company to a syndicate of investors, which gave him more time to work on pet projects. During the next year, the Wright Company merged with two other firms to form the Wright-Martin Company, which created a few new aircraft designs. (The Wright-Martin Company eventually reorganized in 1919 as the Wright Aeronautical Company when aviator Glenn L. Martin left the former firm.) Freed from running a major business, by November of 1916 Orville moved into a new laboratory on North Broadway in Dayton. Over the years, the brothers together, and then Orville alone, had defended the Wright patents with vigor, often defeating defendants in court. However, during World War I, the U.S. government pressured aviation firms to form the Manufacturers Aircraft Association and enter into cross-licensing agreements. Both the Wright-Martin and Curtiss companies received cash settlements for resolving their disputes. The Wright family’s patent war with Glenn Curtiss was over. Other things came to an end as well. In April of 1917, Milton Wright died at the age of 88. And three years later, the oldest Wright sibling, Reuchlin, died in Kansas. Orville’s active role in aviation declined during the early 1920s. But as America’s elder statesman in the field, he still served on various aeronautical boards and committees. For example, from 1926 to 1930, he served with the Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. And from 1920 to 1948, he served on the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. During the summer of 1926, Katharine Wright announced her engagement to newspaper publisher Henry J. Haskell of Kansas City. This news stunned Orville, who somehow had assumed that his sister always would serve by his side in family and public matters. In November of that year, Katharine and Henry married in Oberlin, Ohio, but Orville refused to attend the wedding. Soon after the Haskells married, they moved to Kansas City. Orville remained estranged from his sister until he visited her deathbed in March of 1929. That same year, Wright Aeronautical and the Curtiss Aeroplane Company merged to form Curtiss-Wright, one of America’s largest aircraft and engine companies. Four years later, in November 1932, the federal government dedicated the Wright Memorial Tower at Kill Devil Hill, commemorating Wilbur and Orville’s first four flights. A few years after that, in 1939—after marrying, having a family, and working in Dayton for years—brother Lorin died at age 70. In 1944, Orville took his last airplane flight, more than four decades after his first one. On April 26, he briefly handled the controls of a four-engine Lockheed Constellation, but did no serious flying. Three years later, Edward Deeds, an earlier business partner, planned the Carillon Historical Park for Dayton, and wanted to include in it one of the Wright Flyers. Orville donated to Deeds the 1905 Flyer, the brothers’ first practical aircraft, which had been in storage since 1911 at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Late in 1947, Orville suffered a mild heart attack while doing the routine chore of repairing a doorbell. After a second attack, he died at age 76 on January 30, 1948—the last of the Wright siblings to die. His funeral took place on February 7th. Like Wilbur, he was buried in the family plot at Woodland Cemetery in Dayton. Together or alone, the Wright brothers developed nineteen versions of gliders and airplanes, ran several companies, inspired and trained countless aviators, and helped place the United States at the forefront of aviation science and technology, a position it still holds today. But whatever happened to the original Wright Flyer, the one that Orville piloted into the air in 1903, that suffered elevator damage during its fourth flight late in the day, and soon was rendered useless when a sudden wind sent it tumbling over? In June 1916, after Orville had made major repairs to the machine, he displayed it at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Seven months later, he displayed it again at New York City’s Grand Central Palace during an aviation exhibition. For a few years, the Smithsonian Institute insisted that Samuel P. Langley's airplane—which landed in the Potomac River in early December, 1903—was the first machine capable of sustained flight. Naturally, Orville disputed this claim, so he shipped the Flyer to the Science Museum of London, where it went on display next to an Otto Lilienthal glider. By 1943, Orville and the Smithsonian had made peace, but the Flyer had to await its safe return to the U.S. until after World War II. The original Wright flyer now hangs in the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum for all to see—and for all to marvel at. | ||

| ||

| The Wright Flyer on display at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum. | ||

|

David Langley is a freelance writer who resides in New York. |

Return to Early Index

© The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

All rights reserved.

December 9, 2009.