|

Boeing B-9 Bomber |  |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||

|

Although it was not the first monoplane bomber to be flown by the US Army Air Corps (USAAC), the Boeing B-9 was the first all-metal monoplane bomber used by the air service. The first monoplane bombers were the Douglas B-7 and the Fokker (General Aviation) XB-8, however, they still utilized wood and fabric construction and were conceptually far less advanced than the B-9.1

It was an unsuccessful attempt, by Boeing, to develop a long-range bomber from the Boeing Monomail commercial transport. Immediately it was thought to be a breakthrough in performance, but when orders did not materialize, the project demonstrated the shortcomings of trying to adapt a commercial airplane for military purposes. Germany would also adapt a commercial transport during World War II, the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor, but with limited success. In reverse, several Avro Lancaster bombers were converted as passenger planes after war, but proved to be too uneconomical to operate. Nevertheless, the B-9 did provide some new innovations that would be utilized on the most famous bomber of World War II, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. The B-9 began as a privately funded Boeing project that originated with the development of the single-engine Boeing Monomail commercial transport. It was basically an enlarged twin-engine version of the Monomail, using the same construction techniques which included:

There were two initial models of the B-9, the Model 214 (Y1B-9) and Model 215 (XB-901, YB-9). Both aircraft were identical except for the selection of engines. The Model 214 was powered by Curtiss V-1570 Conqueror engines and the Model 215 was powered by Pratt & Whitney R-1860 Hornet engines.

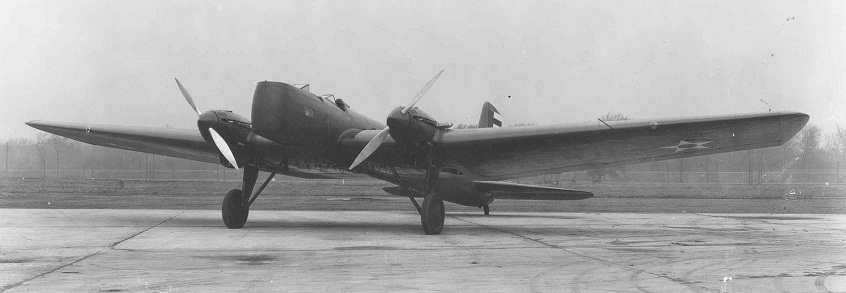

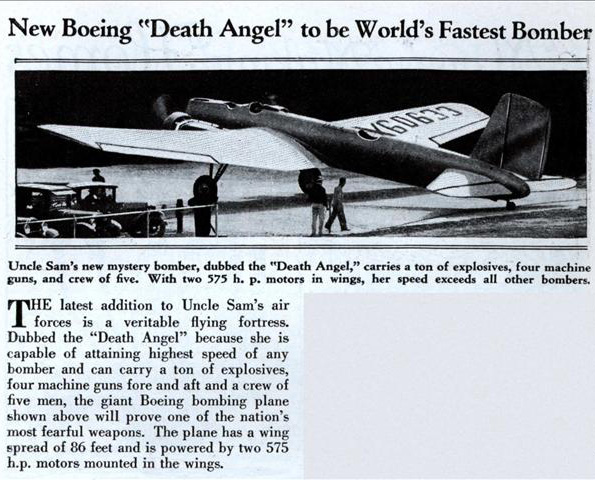

The Boeing B-9 eclipsed the old Keystone biplane bombers. The Model 215 was the first model to fly was and made its inaugural flight on April 29, 1931. This was the period when the USAAC was still taking delivery of Keystone B-6 biplane bombers—the Keystone being the backbone of the American bomber force until 1932. Unofficially, the Boeing YB-9 was known as the "Death Angel" and was praised by Modern Mechanics magazine as "...the World's Fastest Bomber".2 It represented a radical departure in design with its low monoplane wing and semi-retractable landing gear, with wheels that were partly exposed. The design took advantage of new research discovered at the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA), which gave it a tremendous advantage in performance when compared to the old lumbering Keystone biplanes.

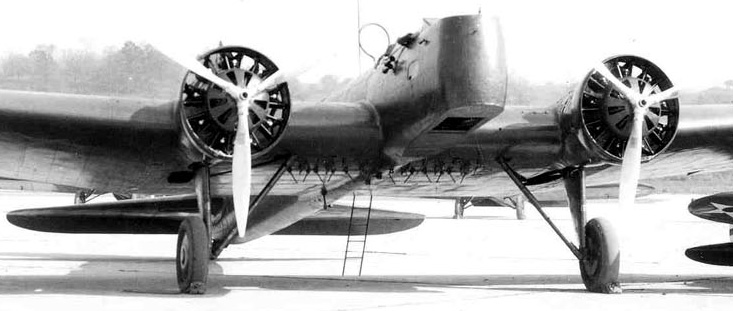

During testing at the 20 foot NACA wind tunnel at Langley Virginia, built in 1927, engineers experimented with a Sperry Messenger and discovered that drag could be decreased by 40% by installing retractable landing gear. Another experiment with a Curtiss Hawk in 1927 demonstrated the advantages of streamlining radial engines with a new NACA engine cowling. The NACA cowling increased airspeed from 118 to 137 mph (200 to 220 km/h). With the release of new data, aircraft manufacturers rushed to install NACA engine cowlings and began designing aircraft with retractable landing gear.3 Another discovery at Langley was the placement of the engines. If not installed on the nose, engines were normally placed either above or below the wing or slung between the upper-wing and lower-wing on twin-engine biplanes. Additionally, external struts supported the landing gear below the fuselage. All this external bracing caused tremendous drag! NACA engineers tried different engine configurations in order to decrease drag and they found the best configuration was to place the engines directly in front of the wing inside of a streamlined nacelle.4 This arrangement also allowed for a low-wing which permitted a retractable landing gear that could retract inside of the wing. As drag was eliminated, performance increased dramatically, which Boeing engineers incorporated into the B-9 design. While the Keystone B-6 lumbered along at 120 mph (193 km/h), the new Boeing YB-9 was able to fly at an airspeed of 163 mph (262 km/h)—an increase of 35%. |

| The Model 215 (XB-901) was the first to be tested by the Army as Boeing property. The airplane was given the standard Army designation of B-9 and was purchased later that year. It was evaluated as the YB-9, powered with Pratt & Whitney Hornet engines and had a top speed of 163 mph (262 km/h). |

The Y1B-9 was evaluated with liquid-cooled Curtiss Conqueror engines. |

|

The Model 214 (Y1B-9) was the second test model and was originally powered by Curtiss Conqueror engines. The increased power from these engines, combined with streamlined engine nacelles, increased its top speed to 173 mph (278 km/h). With the exception of the

Curtiss B-2 Condor, liquid-cooled engines were never used on production US military bombers, as air-cooled radial engines were lighter and considered to be more reliable than liquid-cooled engines. Also, air-cooled radials are generally less vulnerable to damage from enemy air attacks. Liquid-cooled engines were prone to losing coolant, resulting in overheating. After further evaluation, the Model 214 was later converted to Hornet engines.

The Model 246 (Y1B-9A) was powered with improved 600 hp (447 kW) Hornet engines and airspeed increased to 186 mph (300 km/h). |

|

The Model 246 (Y1B-9A) was an improved version over the YB-9 which featured more powerful 600 hp (447 kW) Hornet engines and a redesigned vertical stabilizer. The new engines increased the Y1B-9A's airspeed to 186 mph (300 km/h). It now equaled the speed of all existing American fighter aircraft! To protect the flight crews from the increased speed, enclosed canopies were built, but were never installed. Early pilots preferred open cockpits and were still reluctant to trust their instruments.

In 1931, Boeing B-9 was referred to as "...veritable flying fortress." Despite being advanced, there were several deficiencies with the B-9. For one thing, it was lightly armored. In 1931, “Modern Mechanics” magazine described it as a “...veritable flying fortress”, but this was hardly the case. Armament consisted of only two Browning 0.30 caliber machine guns, which would have been wholly inadequate for its defense. Even the Keystone bombers were armed with at least three guns. With only two guns to defend itself, the B-9s only defense would have been its superior speed, but speed matters very little in a head-on attack. Head-on attacks would become a big problem for B-17s during World War II, even when armed with eleven guns. Head-on attacks would finally be addressed by installing a Bendix chin turret installed under the nose on the B-17G. |

Four 600 lbs. bombs were carried externally at attach points under the center wing. |

|

However, the biggest problem for the B-9 was that it had no internal bomb bay.5 The total disposable bomb load was 2,400 lbs. (1,088 kg), which consisted of four 600 lbs. (272 kg) bombs carried externally at attach points under the center wing. With bombs loaded externally, this created a substantial penalty in speed. Germany also ran into this situation, after the Messerschmitt Me 262 was converted to a jet bomber. Without an internal bomb bay, bombers lose any speed advantage they may have until they drop their loads. This makes them more susceptible to airborne attack. In order for Boeing to design an internal bomb bay for the B-9, it would have required a costly redesign of the fuselage structure, which Boeing was hoping to avoid. As it turned out, the shortcut to create a bomber from a mail-plane just didn’t work. And after Martin came out with the XB-907 bomber in early 1932, Martin received the production order for the new USAAC bomber and the Boeing B-9 became a distant memory.

Summary

The Boeing B-9 was eclipsed by the Martin B-10 bomber. Boeing always hoped that it would receive large orders for the airplane since the B-9 was a great advance over previous USAAC bombers. Although it was a milestone in aircraft design, it was quickly eclipsed by the Martin B-10 bomber. The Glenn L. Martin company in Baltimore, Maryland had brought out a competing design of its own, the XB-907. The XB-907 was slightly larger than the XB-901 and had better performance. It also featured enclosed cockpits, an internal bomb-bay and rotating gun turrets. The Army decided to order the Martin design into production under the designation B-10 and B-12, and no production examples of the B-9 were ordered. The last B-9 was delivered on March 20, 1933. The total production was seven aircraft. It wouldn’t be until the introduction of the next Boeing aircraft where Boeing would play a dominant role in the production of bomber aircraft. Boeing had gotten the message and designed a military bomber from the ground up. The result was the most famous all World War II bombers, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. Boeing B-9 Construction The fuselage was of semi-monocoque construction, which created a nearly circular cross section and increased streamlining. The flight controls required servo tabs to assist pilots in moving the flight controls due to higher airspeeds and greater loads on the control surfaces. This was the first time servo tabs were used on an American aircraft.6 The tail featured a high-reaching vertical fin with low-set tailplanes. The undercarriage retracted though the main legs only partially under the wings while the tail wheel was non-retractable. There were five crew members. Starting from the nose their positions were:

The Y1B-9A carried a crew of five, all seated in separate open cockpits along the length of the fuselage. Despite the increased speed, all of the crew sat in open cockpits except for the radio operator in a station forward and below the pilot. Defensive armament consisted of two Browning 0.30 caliber machine guns. The bombardier’s nose cockpit was equipped with a bomb site and aiming window and also a flexible 0.30 caliber gun at the top. The crew sat in tandem cockpits rather than side-by-side due to the narrowness of the fuselage. The rear gunner operated a single flexible 0.30-inch machine gun, located on top of the fuselage and aft of the wing. The wide separation of crew members created difficulty in communicating with each other in flight. The pilot’s visibility was limited due to the position of the radial engines on each side and the long forward fuselage immediately ahead. At a cruise speed of 158 mph (255 km/h), it had a maximum range of 1,150 miles (1,850 km) and had an operational service ceiling of 20,150 feet (6,140 m). |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Boeing Y1B-9A Bomber | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 76 ft 10 in (23.40 m) |

| Length: | 51 ft 6 in (15.70 m) |

| Height: | 12 ft 8 in (3.86 m) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 8,941 lb (4,056 kg) |

| Max T/O: | 14,320 lb (6,500 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 188 mph (302 km/h) |

| Cruise Speed: | 165 mph (265 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 20,750 ft (6,325 m) |

| Range: | 540 miles (870 km) |

| Powerplant: | |

| Two 600 hp (447 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1860-11 Hornet radial engines. | |

| Armament: | |

|

Two Browning 0.30 caliber (7.62 mm) machine guns and 2,400 lb (1,089 kg) bombs |

Endnotes:

|

Return to Aircraft Index

©Larry Dwyer. The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created November 12, 2009. Updated September 29, 2015.