|

|

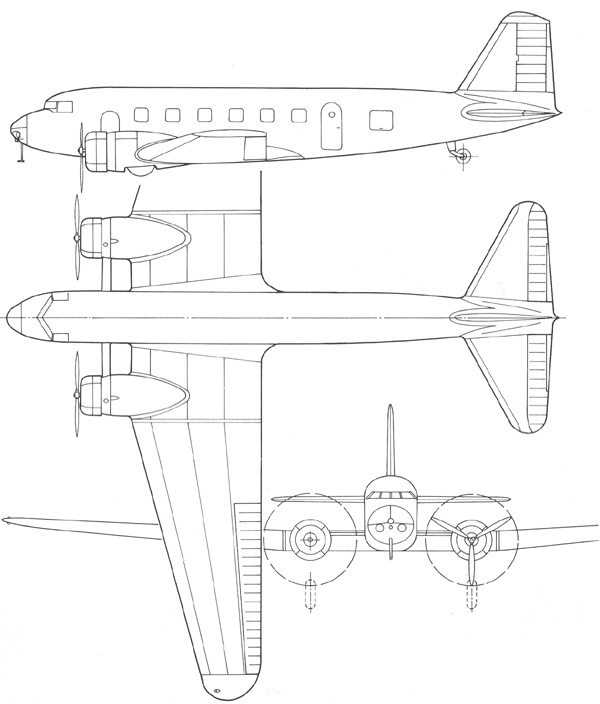

Douglas DC-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||

|

The early 1930s saw a complete transformation of commercial air transport with the introduction of the Boeing Model 247. At last, the majestic but lumbering Curtiss T-32 Condor biplane, the Fokker F VII and Ford tri-motors were giving way to the sleek, all-metal airliners. But something even greater would follow—it was the Douglas DC-3. Hardly had the Model 247 gotten off the ground, when it was eclipsed by the Douglas airliner. And who would have thought that DC-3 would still be in service more than 80 years after it was first introduced, while the Model 247 is only a distant memory. After the crash of Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA) Fokker F-10A NC999E on March 31, 1931, on which the famous football coach Knute Rockne was killed, the Bureau of Air Commerce required all operators of wooden spar and rib aircraft to perform periodic internal safety inspections of their aircraft. Due to the cost and lengthy time for the inspections, TWA needed to update its fleet. It wanted to purchase the Boeing Model 247, however, Boeing had already guaranteed delivery of the first 60 airplanes to United Airlines. Since United was partly owned by Boeing, they were given preference and TWA would have a long wait for the delivery of new aircraft. This gave a huge market advantage to United and TWA couldn’t afford to wait. As a consequence, TWA approached manufacturers Consolidated, Curtiss, General Aviation, Martin and Douglas for a similar design. TWA's requirements were as follows:

• All-metal, tri-motor, monoplane powered by 500-550 hp supercharged engines. The most stringent requirement was that the airplane had to maintain control during takeoff on a single engine, at any airport in its network. Considering that one of TWA's stations was located at Albuquerque, NM, which has an elevation of 4,954 ft (1,510 m) and temperatures often exceed 90° F (32° C), this was no small detail.1 |

The DC-1 was developed at the request of TWA. |

| After weeks of technical negotiations, a contract was finally offered to Douglas. The Douglas design team was headed by Donald Douglas, James H. “Dutch” Kindelberger, Arthur E. Raymond, Ed Burton, Jack Northrop, George Strompl and Fred Herman. James “Dutch” Kindelberger would later form his own company and design the famous North American P-51 Mustang and Jack Northrop, who was the chief engineer on the Lockheed Vega. Many of these men worked with Douglas at the Glenn L. Martin Company and joined him later after he decided to start his own company. Rather than building a trimotor, they convinced TWA that two 710 hp Wright Cyclone engines would meet their requirements. Also included in the design were NACA cowlings, landing gear that would retract into the engine nacelles, and a multi-spar wing, inspired by Jack Northrop that would give the airplane exceptional strength with a long fatigue free life.2 |

|

The result was the DC-1, Douglas Commercial Model No. 1, which in many ways a more refined aircraft than the Model 247. It was larger, faster and carried 12 passengers—the Model 247 only held ten passengers. Also the mid-wing section was integral to the fuselage, which eliminated the spar running through the cabin as it did on the 247. TWA agreed to pay $125,000 towards the cost for the DC-1, and Douglas paid the balance for design and engineering. The total cost for development was $307,000.

A multi-spar wing was the inspiration of Jack Northrop. Its inaugural flight was on July 1, 1933, but it was nearly the last when both engines quit during the climb out. Chief test pilot Carl A. Cover and copilot Fred Herman were able to maintain control as the plane nosed over when unexpectedly, both engines started working again. They resumed climbing and the engines quit again. This happened several times until they were able to gain enough altitude and nurse the airplane back to the airport. As it turned out, the fuel lines were located at the rear of the carburetor and the carburetor floats were also hinged at the rear. Since the fuel was gravity fed and there was no pressure fuel system, the fuel lines emptied and starved the engines of fuel during climb. The problem was corrected by reversing the carburetor floats and fuel lines.3 After the fuel system was rectified, the DC-1 was put through extensive testing. On one flight, it was loaded to 18,000 lbs. using sandbags and lead ingots to simulate full fuel, passengers, crew and mail. It climbed above 22,000 ft, far above the TWA requirement. With a full load, the airplane could takeoff in less than 1,000 ft and with full flaps, it could land at less than 65 mph as required. On one high speed run, it achieved a maximum speed of 227 mph. There was only one more test that had to be completed and that was for the airplane to takeoff and land on one engine with a full load. On September 4, 1933, a test flight was performed from Winslow Arizona to Albuquerque, New Mexico. During the takeoff run, one of the engines had been shut down and the DC-1 climbed slowly from 4,500 ft to its cruising altitude of 8,000 ft. It flew the 280 mile route successfully, thus completing all of the TWA’s requirements. Based on the results of the performance tests, TWA placed an immediate order for 25 Douglas airliners, but with more refinements as the DC-2.

The DC-2 was increased in size with a wider diameter fuselage to allow for the taller passengers to stand in the cabin. Its length was increased by two feet to allow for an extra row of seats that increased total seating to 14. There were other improvements as well. The payload was increased, the service ceiling was increased, the speed was increased and even in-flight movies were introduced. The DC-2 was now the most luxurious airliner in the world. Only four months after the Model 247 entered service, the first DC-2 was handed over to TWA. It flew in record time between Los Angeles and New York. TWA advertised Coast-to-Coast service in a 200 mph luxury airliner called the Sky Chief. Transcontinental flights consisted of four legs from New York (Newark) to Chicago, Kansas City, Albuquerque and Los Angeles. Flights left at 4:00 p.m. and arrived at 7:00 a.m. the next day.

The Douglas DC-2 began operations in July 1934. The Douglas DC-2 production model began operations in July 1934 and after its introduction, it became the best passenger aircraft in the world and other operators soon began queuing up to place orders. Douglas was not about to make the make the mistake that Boeing made by withholding Model 247 orders from other customers. The first of the non-US airline customers was KLM, which began flying the type in the autumn of the same year and the DC-2 was set up for a long production run. In 1934, a DC-2, operated by KLM Airlines, was entered in the MacRobertson Air Race from London to Melbourne, Australia. It came in second against a specially built de Havilland DH.88 Comet, but more importantly, it beat out its rival, a Boeing Model 247D flown by Col. Roscoe Turner and Clyde Pangbourne. The DC-2 was a standard commercial transport that followed a normal commercial route that was 1,230 miles longer than the route taken by the Comet. It also carried a crew of four, three paying passengers and 420 lbs. of cargo. Although it came in second, it demonstrated that a new era in commercial aviation had begun. While the Europeans had focused their attention on military aircraft, the Americans had been steadily improving commercial aviation with hundreds of airliners that were faster than any plane in regular service with the RAF. There was no European equivalent to the DC-2.4

Donald Douglas Receives Collier Trophy, 1935. In 1935, the DC-2 became the first Douglas aircraft to receive the prestigious Collier Trophy for outstanding achievements in flight. Douglas built 156 DC-2s at its Santa Monica plant in California and a total of 193 DC-2s were built. Further improvements were made when Douglas attempted to fulfill yet another requirement, this time from American Airlines. American operated Curtiss T-32 Condor sleeper aircraft on its transcontinental flights. Wanting to keep abreast of the latest developments, they asked Douglas for still larger version of the DC-2, which resulted in the DC-3. The DC-3 prototype first flew on December 17, 1935, and the design was soon being produced in two versions for American Airlines, the 14-passenger DST sleeper and a 21-seat 'daytime' airliner. Services with DC-3s began in June 1936.

What was to become perhaps the most important airliner in history, quickly established its reputation with this and other operators, including the military. During World War II, the DC-3 (named Dakota by Britain) was mass produced as a utility transport in C-47, C-53, and other versions, known also as Skytrains and Skytroopers, and was license-built in large numbers in Russia as the Lisunou Li-2. Used in all imaginable roles, from freight and personnel transport to glider tug and ambulance, the type was active in all theaters of war, notably during the D-Day landings in Normandy, and subsequent assaults by Allied airborne forces. After the war, military flying continued and production of the civil version was restarted. DC-3s became the mainstay of worldwide passenger and freight services for many years. As larger capacity piston and jet airliners became available, DC-3s were gradually turned over to smaller operators. |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Douglas DC-3A | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 95 ft 2 in (29.00 m) |

| Length: | 64 ft 8 in (19.70 m) |

| Height: | 16 ft 11 in (5.16 m) |

| Weight: | |

| Empty: | 16,865 lbs (7,650 kg) |

| Gross: | 25,199 lbs (11,430 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 230 mph (370 km/h) @ 8,600 ft. (2,590 m) |

| Cruise Speed: | 207 mph (333 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 23,200 ft (7,100 m) |

| Powerplant: | |

| Two 1,100 hp (820 kW) Wright R-1820 Cyclone, 9 cylinder, radial engines. | |

Endnotes:

|

1. Rene J. Francillon. McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920: Volume I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1988. 150. 2. Douglas J. Ingells. The McDonnell Douglas Story. Fallbrook, California: Aero Publishers, Inc., 1979. 45-46. 3. Ibid. 48. 4. Philip Jarrett, ed. Biplane to Monoplane, Aircraft Development 1919-39. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1997. 20. |

© Larry Dwyer. The Aviation History Online Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created October 3, 1998. Updated November 24, 2014.