|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

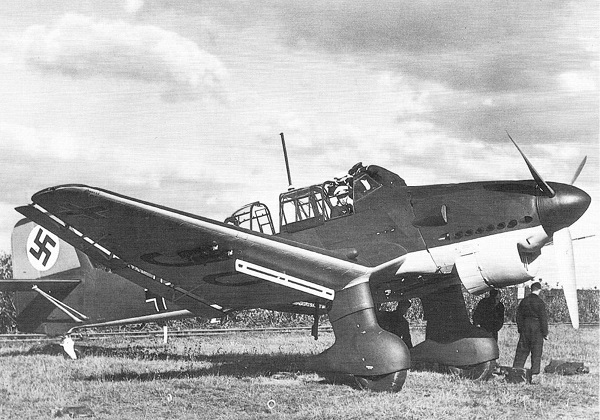

| Junkers Ju 87 Stuka |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||

|

It was the scourge of World War II and no other aircraft terrorized its victims as much as the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka. Stuka was an abbreviated form of Sturzkampfflugzeug or literally "diving fighting plane". Only later was it applied specifically to the Ju 87 Stuka. So to name a plane Stuka would be the equivalent of naming the P-51 "Fighter" or B-17 "Bomber" but in any event, the name stuck.

It made its combat debut with the Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War and was extremely accurate against ground targets. For the German commanders, the Stuka was their flying artillery. It was instantly recognizable with its inverted gull wings, fixed spatted undercarriage and infamous Jericho-Trompete ("Jericho Trumpet") wailing siren, a psychological weapon used to terrify ground troops. A French general remarked that French artillerymen simply stopped firing and went to the ground, the infantry cowered in the trenches, dazed by the crash of bombs and the shriek of the dive bombers. However, some Stuka pilots found the siren annoying just as much as the ground troops and deactivated them and by 1943 the siren was discontinued. However, the Stuka was vulnerable to the more nimble fighters of the day, such as the Spitfire and Hurricane, and required fighter top-cover for protection in order to complete its missions successfully. First flown on September 17, 1935, it was already considered obsolete at the start of World War II. However, because of its early success and with no other alternative readily available, it would remain in production until almost the end of the war. The concept of dive-bombing didn’t begin in World War II as is often believed. Its origins began in world War I with the British who first tried it with moderate-dive angle attacks, followed by the Americans and Japanese who experimented with dive-bombing between the wars. Early on, the biplane was considered the optimum tactical weapon with a terminal velocity slow enough for pin-point accuracy and pull-out requirements, but World War II became the first real proving ground for the dive-bomber. |

| It has been often told that it was designed by Junkers, at the insistence of Ernst Udet, who pushed it to the forefront of German aviation development. After observing Curtiss Hawks dive-bombers at a Cleveland air show in 1933, Udet brought two Curtiss BFC-1 Hawks back to Germany and provided his own show. He dove from 1,000 m (3,280 ft) releasing his bombs at 100 m (330 ft), before pulling out.1 At least that was the myth. |

|

In reality, the Stuka design had already been finalized and was in the mock-up stage before Udet became enamored with the Curtiss Hawk. Also he never did airshow bombing, just crowd-pleasing aerobatics, but he was a fervent supporter of vertical dive-bombing. In contrast, Maj. Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, cousin of the famous World War I ace, feared that such high-level nerves and skill could not be expected of the average Luftwaffe pilot, and he canceled the Ju 87 program. Richthofen thought that the slow and cumbersome dive-bomber would never survive the onslaught of anti-aircraft fire that was likely to be encountered. Another aspect was that, in an era before the G suit was invented, many pilots were likely to black-out while recovering from a 5+ G dive. However, he was overridden by the Chief of the Luftwaffe Command Office, Walther Wever, and the Secretary of State for Aviation, Erhard Milch. Publicly, the Luftwaffe rejected Udet’s (a civilian pilot at the time) idea and enthusiasm, because it would be a violation of the Treaty of Versailles. However, secretly they were preparing to adopt the Stuka concept. They saw in the new plane, a great opportunity to improve the accuracy of bombing. A few Stukas could achieve much better results than an entire squadron of horizontal bombers.2 In the end, Udet replaced Richthofen, and his first order was to restore the Ju 87 program.

A Stuka shown with its dive-brakes fully deployed. The Stuka would have to be strong enough to withstand a 360 mph (580 km/h) dive and required dive-brakes to prevent the airplane from exceeding speeds to where it could be operated safely. To meet these criteria, the Stuka incorporated an interesting feature which consisted of automatic pull-up system, which leveled the plane out even if the pilot blacked out during the dive maneuver. Experience showed that about half of the pilots would black out when pulling 5+ Gs to recover. The system worked by rolling the aircraft 180 degrees, into a 60-90 degree dive, whereby the dive brakes would extend and activate the automatic recovery system. When the aircraft reached 1,500 ft. (457 m), a red light would flash on the instrument panel for the pilot to release the bomb. He would then press a trigger on the control stick and the bomb would be released via a swiveling mechanism, below the fuselage, which allowed the bomb to clear the propeller. After the bomb was released, the dive flaps would automatically retract, the propeller pitch would change, and the controls would automatically pull the plane out of the dive and into a fast climb. The only thing the pilot had to do was to aim the aircraft at the target. Once the plane’s nose came up above the horizon, he could take control again. This system is why the Stuka became such a devastating weapon.3 However, the system was not fail-safe and during training in the Baltic while aiming at a floating target, at least three airplanes did not recover and drove straight into the sea. Not trusting the automatic system, many pilots chose to control the airplane manually through the entire dive maneuver.

Junkers K 47. In April 1935, the firms of Arado, Blöhm und Voss, Heinkel, and Junkers were requested to begin work on dive-bomber prototypes, but Junkers had the advantage with earlier Swedish-built K 47 and K 48 models that had already proven successful in vertical dive tests.4 It was a heavily braced and strutted aircraft powered by a 590 hp (440 kW) Pratt & Whitney Hornet radial engine. Herman Pohlmann designed the K 47 under the direction of Karl Plauth, a WW1 fighter pilot. It was thoroughly tested by Swedish pilots who performed hundreds of dives. After Plauth died in the crash of a Junkers prototype, Pohlmann went on to design the Ju 87. At the start of the war, the Stuka was very effective in France and during the Polish Blitzkrieg (lightning war). It was considered invincible, but what was not quite understood at the time, it excelled only when air superiority had been established. After being challenged by Spitfires and Hurricanes at Dunkirk, they took a severe mauling during the Battle of Britain in 1940. Rather than dive after the Stuka during a bombing run, British fighters would wait until the Stuka pulled out on a predictable recovery path and then strike. Suffering disastrous losses, Stukas were restricted to night-bombing missions and were removed from operations over Western Europe. However, it would suffer just as much later on, at the hands of Russian pilots flying Bell P-39 Airacobras, on the eastern front.5

As the war progressed, the strategy of the land dive-bomber had passed. However, dive-bombers still proved to be successful in the US Navy as can be attested by the success Curtiss SB2C Helldiver, which sunk more ship tonnage than other aircraft during the war. However, the US Army gave up on land dive-bombers, after one major disaster had occurred. Five out of seven A-24 Banshees were shot down by Japanese Zeros, after being sent to attack a Japanese convoy off Buna, New Guinea. A sixth plane was damaged so badly, it never made it back to base. The failure of the mission is attributed to the Army’s failing to provide top cover. Consequently, A-24s were relegated to non-combat duty.6 The Stuka remained the only dedicated land dive-bomber during the war, but it was a slow cumbersome airplane with poor defensive capabilities, that would haunt the German command. Despite its faults, Stukas were still devastating in Yugoslavia, Greece, North Africa and the Caucasus, when not opposed by Allied fighters. They were particularly destructive as an anti-shipping weapon and essentially destroyed the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean fleet. The HMS Illustrious and its support ships were so badly battered off the coast of Malta that it was out action for nearly a year. Stukas were also successful in chasing the Royal Navy out of the waters off Norway.

Captured Ju 87 of the Regia Aeronautica They were also flown by the Regia Aeronautica and it was nicknamed picchiatelli (little woodpecker). The Stuka has often been confused with the Breda 201, which was an Italian built single-seat dive-bomber. While the 201 does bear some resemblance with a less pronounced gull-wing, it differed in all other respects. All Ju 87s that served with the Regia Aeronautica were built in Germany.7 Other users were the Royal Romanian Air Force and Bulgarian Air Force. The role of the dive-bomber would eventually be delegated to faster and far more nimble fighters such as the Focke-Wulf 190. Unlike the Stuka, fighter/bombers could drop their bombs and were able to defend themselves from attack. New bombs sites increased the accuracy of horizontal bombing, matching the precision of the dive-bomber. Oberst Hans-Ulrich Rudel was the most famous of the Stuka pilots and was the only recipient of the Knights Cross with Golden Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds. He flew a record 2,530 combat missions destroying 519 tanks, 150 artillery pieces, 70 landing craft, nine aircraft, several bridges, a destroyer, the Soviet battleship Marat and severely damaged the battleship October Revolution. He was forced down 30 times by artillery and ground fire, and lost a leg in February 1945. He was wounded a total of five times.8 Considering the aircraft’s performance and his length of service, it’s a wonder he survived at all.

The Ju 87 was produced in several variants, with increasing power, longer range and bomb-lifting capability. The Ju 87A was powered with a 630 hp (470 kW) Junkers Jumo 210D. It was underpowered and really wasn’t a combat ready airplane. Typical armament for the Ju 87A consisted of one 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine gun in each wing with 500 rounds of ammunition stored in the undercarriage "spats". The rear gunner operated a single 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 15 with 14 drums, containing 75 rounds each. The Ju 87 was capable of carrying a 500 kg (1,100 lb) bomb, but for most operations, they were limited to a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb load. The Ju 87B was the classic Stuka with a redesigned fuselage, big wheel pants, squared away greenhouse, and vertically louvered, overbite chin radiator. It was fitted with a more powerful 1,200 hp (880 kW) Junkers Jumo 211D engine and could carry a 500 kg (1,100 lb) main bomb. It was intended to be the last model made, but without an alternative replacement, production continued. The JU 87R was a long range and final version of the B. It was used mainly for anti-shipping operations and two 300 L (80 gal) wing drop tanks were installed. The bomb load was normally restricted to a single 250 kg (550 lb) bomb if the aircraft was fully loaded with fuel. The extra fuel increased the range by 360 km (220 mi). The Ju 87D was the most produced variant of 3,639 and was fitted with a more powerful 1,400 hp (1,050 kW) Junkers Jumo 211J engine allowing the bomb load to a increase to 500-1,200 kg (1,100-2,650 lb). The internal fuel capacity was raised to 800 L with the option of retaining the 300 L (80 gal) wing drop tanks. Endurance increased to four hours using the drop tanks.

Near the end of the war, the Ju 87 was finally resurrected as an anti-tank weapon and designated the Ju 87G. Two 30 mm (or 37-mm high-velocity) cannons in underwing pods were installed and it could carry a 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) free-fall bomb. It copied the armored protection of the Ilyushin Il-2 Sturmovik, to protect the crew from ground fire required to conduct low level attacks. It wasn’t an easy airplane to fly, while aiming accurately at ground targets, and only the most experienced pilots were allowed to fly it.9 Not many G models were built. The G-1 was converted from older D-series airframes, retaining the smaller wing, but without the dive brakes. The G-2 was similar to the G-1 except for use of the extended wing of the D-5. 208 G-2s were built and at least a further 22 more were converted from D-3 airframes. Approximately 6,500 aircraft were built, but less than 400 Ju 87 Stukas were in service at any one time. Despite its scarcity, it would leave an indelible impression very much out of proportion to its numbers. |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Junkers Ju 87 (B-2) | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 45 ft 3 in (13.80 m) |

| Length: | 36 ft 1 in (11.00 m) |

| Height: | 13 ft 10.5 in (4.23 m) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 7,086 lb (3,205 kg) |

| Takeoff Weight: | 11,023 lb (5,000 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 242 mph (390 km/h) at 13,410 ft (4,400 m) |

| Service Ceiling: | 26,900 ft (8,200 m) |

| Range: | 311 miles (500 km) |

| Powerplant: | |

| One 1,200 hp (885 kW) Junkers Jumo 211D V-12 engine. | |

| Armament: | |

|

Two forward MG 17 machine guns, one rear cockpit MG 17 machine gun. One 550 lb (250 kg) of fuselage bomb and two 110 lb (50 kg) bombs on each underwing hardpoints. | |

Endnotes:

|

1. David Mondey. The Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. New York: Smithmark Publishers, 1996. 111. 2. Thomas Hajewski. The Stuka Story. Air Force Magazine.: Vol. 70, No. 5, May 1987. 3. John Moffat with Mike Rossiter. I Sank The Bismarck. London: Bantam Press, 2009. 136. 4. J. Richard Smith. Aircraft in Profile, Volume 4, The Junkers Ju 87A & B. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1968. 3. 5. Dmitriy Loza. Attack of the Airacobras. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2002. 217. 6. Rob Stern and Don Greer. SBD Dauntless in Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron Signal Publications, 1984. 17. 7. Johnathon Thompson. Italian Civil and Military Aircraft, 1930-1945. Los Angeles: Aero Publishers Inc., 1963. 42. 8. Günther Fraschka. Knights of the Reich. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1989. 127-130. 9. J. R. Smith & Anthony Kay. German Aircraft of the Second World War. London: Putnam, 1985. 392.

Stephan Wilkinson. September 2013 Screaming Birds of Prey. Aviation History. Volume 24, No. 1. 24-31. |

Return to Aircraft Index

©Larry Dwyer. The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created December 29, 2013. Updated May 13, 2021.