|

|

Kayaba HK-1 Flying Wing by Raul Colon |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||

|

During the early days of World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army’s Air Forces had minimal interest in the development of a flying wing configuration airplane. This dramatically contrasted with the view of their main ally, Nazi Germany, who had experimented with tailless flying winged aircraft for several years. The lack of effort by the Japanese Navy, the one service viewed by most as the forerunner in military aviation in Japan, did not imply that the Army would follow them. Indeed, they quickly started a crash design program in late 1939. Because of the late date of their program, the Japanese Army top brass knew that they needed to begin a program that could achieve in short time, with a dwindling financial resource base, the maximum results. Efforts by the Imperial Japanese Army concentrated on the gliders designs of the Kayaba Works Corporation as well as the Mitsubishi Company’s tailless aircraft designs, which copied the German Messerschmitt Me 163 Jet Fighter. |

| The Kayaba’s designs were first conceived to research data on tailless airplanes configurations. Many designs were submitted by engineers inside Kayaba and by outside consultants. The most promising design program was the HK1. The HK1 was the brainchild of a brilliant, albeit, obscure Japanese engineer, Dr. Hidemasa Kimura. He based his design on the concept of Kumazo Hino, the pioneer aviator who was the first person in Japan to fly a plane, in the spring of 1910. Initial tests on the design were promising and lead the Japanese Army to sponsor an aircraft concept program—the first step in establishing a development and production program of a military aircraft. |

Kayaba KU-2. Working closely with Kayaba’s Chief Developing Designer, Dr. Shigeki Naito, Kimura designed and constructed a tailless test model aircraft. The model, designated the KU2, was extensively tested between early November 1940 and May 1941. After the test phase of the KU2 was over, Dr. Kimura, with the assistance of another brilliant Japanese engineer, Joji Washimi, began to work on a more advance design in the spring of 1941, the KU3. The KU3 was a two-system experimental model, it had no vertical control surfaces and the edges of its wings were cranked incorporating sections of different angles of sweepback. The KU3 had a three-control array, along the trailing edge of each wing. The KU3 made 65 test flights before the only prototype model crash landed in late 1941.

Kayaba KU-3. Kimura wasn’t done with flying wings. He took the data recollected on KU3 program and used it to build the first Japanese powered flying wing aircraft, the KU4. At this moment for Japan, time was running out and Kayaba had not shown concrete results to merit further investment in resources. Japanese limited resources were needed in other areas. The tide of war had turn against the Empire. The KU4 program was terminated by the Army as soon as the drawings were on the table. This marked the end of any official Japanese founded research on a tailless flying wing design. Then in 1944, with the appearance of America’s massive Boeing B-29 bombers on the skies over Japan’s Home Island, changed the equation. The Japanese Army, now with the complete support of the Navy, restarted the flying wing program.

The Mitsubishi J8M-1 Shusui for the Navy and Ki-200 for the Army. The need for a high flying interceptor plane to take out the B-29s became imperative. The Army knew time was running out, and turned to the Germans for help. They knew that any aircraft development program would take years to produce a serviceable plane, and in the case of a radical design such as a flying wing, the development process could take at least a decade. With this situation on their minds, the Japanese Navy leadership decided that the only route available to them was to copy the only successfully operational flying wing design program in the world, Germany’s Messerschmitt Me 163 Jet Fighter. The Mitsubishi Company, using German supplied Me 163 Operational Manuals as well as a Walter HWK 109-509 rocket propelled engine, was selected for the job of interpreting the data given by the Germans. They promptly went to work on a design for the new tailless flying wing airplane. In a matter of only months, thanks to the assistance of German engineers, Mitsubishi produce a test plane version of what they thought it would be the next great Japanese plane. The J8M-1 Shusui (Swinging Sword) was ushered in late December 1944. Mitsubishi built first a glider version for data collection purposes. It first took to the air around mid January 1945 and was subsequently placed in full prototype production mode. Two prototypes models were designated for the two services, the mentioned J8M-1 for the Navy and the Army’s Ki-200.

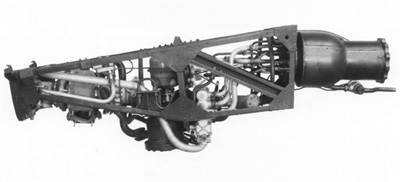

Walter HWK 109-509 rocket engine. Pilots started taxi-run practices with the J8M-1 at Kashima Air Base in the spring of 1945. Rigorous testing and practice runs were made at Kashima by Navy pilots in preparation for the day when the Walter rocket engines would be fitted on the J8M-1 and the aircraft could take-off on their on power. The first J8M-1, fitted with the Walter engine, first took to the air in the morning of June 7th, 1945. A catastrophic engine failure shortly after takeoff resulted in a massive crash and subsequent explosion. The test pilot was killed instantly. This crash and the end of the war (two months later), spelled the end of the minimal Japanese attempt of acquiring a flying wing fighter. The J8M-1 never entered production, and the next generation Ki-202 flying wing advance fighter never made it off the drawing board. When the Allies entered Japan in August 1945, they discovered, to their relief, a crude flying wing program, a program that was doomed before it could takeoff. |

|

The author Paul Colon is a freelance writer who resides in San Juan Puerto Rico. rcolonfrias@yahoo.com |

©Raul Colon. The Aviation History On-Line Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created December 3, 2007. Updated October 26, 2013.