|

|

Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer by Dennis Baer |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||

|

| ||

|

Having belatedly, come to the conclusion that sea plane hulls were not compatible with efficient airframe aerodynamics, the U.S. Navy added land based patrol aircraft to their air arm in early WWII. Before the war, the Army Air Corp had set Navy brassís teeth on edge by using their early Boeing B-17 bombers to demonstrate long range interception of inbound surface ships. The Navy had countered this threat to their monopoly on defending America's coasts by getting the War Department to ban any maritime patrols by Army bombers that were more than 100 miles from shore. This bit of foolishness was instantly forgotten when Nazi submarines began sinking Allied trans-Atlantic shipping in record numbers.

Being late to the party, the Navy had to accept Consolidated B-24 Liberators as patrol planes. The sleeker, easier to fly B-17s were all reserved for Army Air Corp use. Eager to reduce crew fatigue on long patrols, Consolidated was instructed to allocate three B-24s for conversion to Navy requirements. To ease control problems, Consolidated had already attempted to change the B-24's twin rudders to a single vertical fin. The first conversion, the XB-24K, done at the Consolidated San Diego plant used the tail from a Douglas B-23 Dragon. The results were unsatisfactory. |

| The Ford Motor Company, which operated a huge B-24 license-production plant called Willow Run in Michigan, then transplanted a vertical fin from a C-54 transport onto one of their B-24s, creating the XB-24N. They also added a new custom built horizontal fin and replacing the nose turret with an ERCO 250 SH ball turret, which was more streamlined than the standard nose turret of production B-24s. It was superior enough to the standard B-24J that the Army ordered seven more pre-production YB-24Ns and inked an order for 5,168 B-24N bombers. Horrified that a mere car manufacturer might have upstaged them, Consolidated pulled strings to have this order canceled. Equally horrified that they might be forced to accept some of these planes instead of getting their own design, the Navy helped to kill the N-model. |

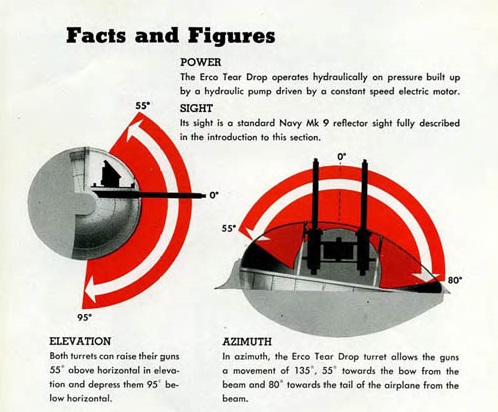

Changes from the B-24 included a single vertical fin and replacing the nose turret which was more streamlined than standard models. The forward fuselage was lengthened and there were changes in armament. The Privateer used the same wing and landing gear as the B-24. Meanwhile, new fuselages were constructed for the Navy PB4Y-2s in San Diego. For the second time, the basic Liberator fuselage was lengthened (legendary founder of Consolidated, Ruben Fleet personally ordered the first B-24C and all subsequent Liberators to have the nose section lengthened 2 feet, 7 inches at company expense "to improve the appearance." He could have saved the effort; it was still a homely plane). The new fuselage was now a full 74 ft, 7 inches, 10 feet 5 inches longer than the first B-24A. The space was devoted to new electronics and a flight engineerís station. The first three Privateers (the initial name "Sea-Liberator" had been quickly dropped) flew with standard twin tails. When the new single tail was ready, it caused the Privateer to tower a hanger-roof-scraping 29 feet 1 5/8 inches off the floor. A second dorsal turret was fitted with twin .50 caliber machine guns, as well as a pair of ERCO 250 THE turrets which replaced the two flexible, hand held guns of the Liberator's waist gunners. The Navy, in it's infinite wisdom, noted that the teardrop shaped waist turrets could be depressed downward to such a degree that the fields of fire from these guns converged at a point 30 feet below the belly of the plane. For this reason, no belly turret was fitted.

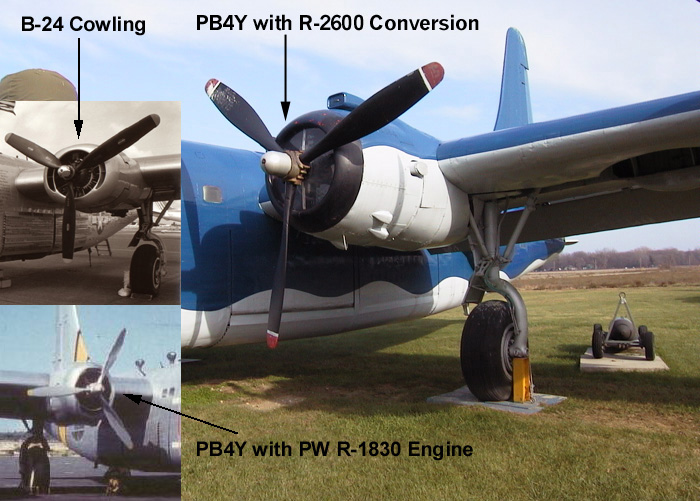

The trademark of the Liberator family, the 110 foot long, twin spar Davis High Lift wing with it's massive Fowler flaps was unchanged. This was the secret to the long range and relatively high speed of the Liberator/Privateer family, and the reason the Privateer stayed on in squadron service long after the rival B-17 had been retired. Four Pratt & Whitney R-1830-94 engines were retained although they were fitted with only a single stage supercharger. As low altitude patrol planes, the two stage supercharger was considered unnecessary. The oil cooler air inlets were moved to above and below the engine, eliminating the characteristic horizontal oval appearance of the engine cowl. Military and T.O. power was rated at 1,350 hp (1,000 kW) each. Later, when some survivors of Navy and Coast Guard service were modified for use as fire bombers, they were fitted with 1,700 hp (1,270 kW) Wright R-2600 engines. |

|

|

The two distinguishing features between the B-24 and the Privateer were the tail configurations and the engine cowlings. Cowling configurations for the oil coolers differed depending on the engine installation.

|

|

Twelve .50 caliber Colt-Browning M2 machine guns were carried, all in powered turrets. This was sometimes augmented with one or two 20 mm nose cannons for strafing. Normal bomb load for a 1,300 mile radius patrol was 4,000 pounds of bombs, depth charges or mines. Some planes were also armed with one or two ASM-N-2 Bat anti-shipping glide bombs which was first used successfully during a raid against Japanese shipping in Valikpapan Harbor, Borneo in April of 1945.

Operationally, the classic use of patrol bombers is to hunt down and sink enemy ships. The Privateer stepped easily into this role, the way having been paved by years of anti-submarine and anti-ship operations in Navy PB4Y-1 Liberators and USAAF B-24s equipped with a series of radar sets collectively known as "Low Altitude Bombing" sets. By WWII standards, the Privateer was lavishly equipped with an electronic suite that could be customized on a mix and match basis so that Privateers could be airborne communication platforms, radar and radio station hunter/killers, anti shipping search and destroy units, weather reconnaissance planes or search and rescue units to locate downed airmen with their radio direction finders. If the situation demanded, they could even act as their own standoff anti radar jamming unit. Patrol craft are not glamorous, like fighter planes, or vital to the troops on the ground like bombers, close support attack planes, or the cargo planes that keep them supplied. What the Privateer lacked in pizzazz, it more than made up for in versatility and practicality. The Navy wanted the seas swept clear of enemy transport, enemy radars, enemy radio navigation aids, and enemy scouting vessels. It wanted mines planted, submarines harassed or destroyed, communications augmented and weather information for 1,300 miles around the Privateer's base. No other aircraft was as capable of this as the Privateer . The last Privateer was delivered in October of 1945. Of 739 airframes built, there may be two in flying condition today. After WWII, Privateers were used as hurricane hunters and played a large role in Reserve squadrons, helping to keep up training for thousands of Naval Reservists. In 1950, numerous mothballed Privateers were recalled for service in Korea, where their air-to-surface radar was used to hunt down and destroy North Korean infiltrators along the coasts. They also flew dangerous nighttime Firefly missions to drop flares over embattled United Nations troops so that air support could continue around the clock. |

|

|

The US Coast Guard removed the side and nose turrets and rebuilt the nose of the plane with a huge glazed observation dome.

|

|

Other Cold War missions included the theoretical deliver of nuclear weapons by Naval aircraft and an unspecified number of PB4Y-2s were modified to deliver second generation atomic bombs. Other airframes were optimized for Ferret missions to gather electronic intelligence. These are high value/high risk missions, often employing a long series of uncomfortable, tension filled runs aimed at approaching or penetrating enemy territory to eavesdrop on enemy radar signals or radio traffic. Most valuable for intelligence analysts is the air-to-ground and air-to-air communication between interceptor controllers and interceptor pilots. The easiest way to get this chatter is to provoke the enemy air defenses into launching an interception of your own aircraft. The hard part is getting away alive after they do. On April 8th, 1950 a Privateer from VP-26 was caught by Soviet MiGs over the Baltic Sea and destroyed with all crewmembers either killed in the crash or strafed to death. Apparently a number of the 38 Privateers seconded to the Nationalist Chinese Air Force suffered similar fates at the hands of the Red Chinese People's Army Air Force.

Other post war service included 22 Privateers provided to Aeronautique Navale for service with the French colonial forces in Vietnam. They were used as bombers until after Dien Bien Phu, with four lost in combat. Six were returned to U.S. service, the remaining twelve were flown to North Africa where they fought in Algeria and later during the Suez Incident. In 1961, the survivors were scrapped in favor of new Lockheed P2V Neptunes, a fate shared by most other Privateers. The longest serving Navy Privateers were expended as a radio control target drones off Point Magu, California in the early 1960's. The last, flying under the call sign Opposite 31 and carrying the ironic nickname Lucky Pierre was shot down by an Bullpup missile with an experimental proximity fuse that turned the Bullpup into an air-to-air weapon. The relatively large warhead detonated over the back of the Privateer's wing, sparking a spectacular fireball of burning fuel and marking the end of the Privateer's military career. A small number of ex-US Coast Guard search and rescue Privateers survived to become anti-forest fire water bombers. The Coasties had removed the side and nose turrets and rebuilt the nose of the plane with a huge glazed observation dome. After being sold off as surplus, civilian operators gave them new Wright R-2600 engines along with the installation of their borate/water slurry tanks. These were Super Privateers" and these planes soldiered on into the 1990's. |

|

|

A modified Consolidated PB4Y was donated to the Yankee Air Force Museum in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The starboard turret is missing but Yankee Air Force Museum hopes to replicate the port side. |

| One of these planes (call sign "Tanker 125") was donated to the Yankee Air Force Museum in Ypsilanti, Michigan. You will note from the rear view that only one ERCO 250 THE turret is installed. Unfortunately, only this portside turret was available, the starboard one having been scrapped. Eventually, the museum hopes to build a "mirror image" starboard turret and fit it to this static display plane. |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | 110 ft 0 in (33.53 m) |

| Length: | 74 ft 7 in (22.73 m) |

| Height: | 30 ft 1 in (9.17 m) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 37,485 lb (17,003 kg) |

| Max Gross: | 65,000 lb (29,484 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 237 mph (381 km/h) at 13,750 ft (4,190 m) |

| Performance: | |

| Cruise: | 140 mph (225 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 20,700 ft (6,310 m) |

| Range: | 2,800 miles (4,506 km) |

| Powerplant: | |

|

Four, Pratt & Whitney R-1830-94 Twin Wasp 1,350 hp (1,007 kW), 14-cylinder radial, air cooled engines. | |

| Armament: | |

|

Twelve 0.50 machine guns (nose, turrets, waist and tail positions) Bomb load 12,800 lb (5,806 kg). | |

©Dennis Baer The Aviation History Online Museum.

All rights reserved.

Created March 3, 2008. Updated June 30, 2019.