|

|

North American B-25 Mitchell by Earl Swinhart |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||

|

B-25Js of the 822nd Bomb Squadron, 38th Bomb Group at Ormoc Bay, sunk nine Japanese ships and damaged four. American losses totaled seven aircraft, and eight damaged. (Image used with permission from Dare to Move.) | ||

| Wednesday, July 28, 1943 was a warm day off the island of New Britain in the Bismarck Sea. Three Japanese destroyers were steaming on course 280° over the flat, mirror like water at 20 knots. Suddenly a lookout called "aircraft, low off the port beam!". Another lookout identified the planes as American B-25 bombers, notorious for their "skip bombing" against destroyers. All guns were trained on the interlopers. Suddenly, while the aircraft were still more than a mile (1.6 km) away, a great geyser of water shot up close by the destroyers. The lookouts began frantically searching the sea; there had to be a ship close by with cannon aboard. But there was none! Suddenly, one of the destroyers was hit. It exploded in flames and sank in just a few minutes. Was it possible these aircraft had some new and diabolical weapon? |

| On the contrary; it was the very same old 75 mm M-4 field cannon used to rout the Germans in WW1! A few months before the incident, Colonel Paul Gunn of the US Fifth Air Force in Australia, had experimented with the installation of a 20 mm cannon in the nose of a B-25. Colonel Gunn, abetted by a North American Aviation Company Tech Rep named Jack Fox, sent the idea to North American in Inglewood, California where it was promptly taken a step further and worked into the installation of the 75 mm cannon. |

North American B-25 Mitchell. General George Kenney called the North American B-25 Mitchell a "War Dog". He should know; he helped write the book on the B-25. General Kenney was commander of the Fifth Air Force in the South Pacific during WWII. Trying to fight off the Japanese in a "secondary combat theater" (as the Pacific war was regarded) meant "making do, with what you had". Prosecuting the war against Japan called for a lot of ingenuity. Kenney was forced to use what he could scrape together and make effective. He came up with the ideas and "Pappy" Gunn put the ideas to work. One of the first ideas was the installation of a machine gun "pack". The bombardiers compartment was removed and replaced with four Browning M2 .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns in the nose of the Mitchell and four more in blisters on the sides of the craft. The B-25 became an awesome strafing machine with eight forward firing guns. Later, they rigged a lock for the top turret making a total of ten .50 cal (12.7 mm) machine guns, all lit off simultaneously by one finger of the pilot! Then came the installation of the 75 mm cannon. It required a crewman to load, fire and extract the casing. And when it fired it felt like the aircraft had "hit a brick wall", but with its 2.95 inch (75 mm) projectile, it could turn a tank into scrap metal and punch very large holes in Japanese destroyers and barges at a range of nearly 2 miles. The Japanese paid dearly for the ideas of Kenney and the ingenuity of Gunn.

Take off from the deck of the USS HORNET of an Army B-25 on its way to take part in first U.S. air raid on Japan. Doolittle Raid, April 1942. The North American B-25 Mitchell owed its beginnings to the Army's quest for a medium bomber. The Douglas B-18 "Bolo" was designed and built by Douglas Aircraft in 1937 and North American responded to this by designing and building the larger and more powerful B-21 "Dragon" that same year. Both of these aircraft were twin engine "tail dragger" types. Unsatisfied with performance only marginally better than single engine aircraft, the US Army Air Corps issued Proposal Circular #38-385 which was sent to all major aircraft manufacturers in March 1938. It contained the requirements for an "Aircraft - Bombardment Type - Medium". This would fill a gap in the bombing aircraft types between the light bomber and four engine heavy bomber. A total of 5 manufacturers submitted designs (North American, Douglas, Martin, Stearman and Bell) and all but one built prototypes. North American submitted their "Design NA-40" to the USAAC and shortly afterward built the NA-40B prototype. It was a sleek looking twin engine, twin tail machine with tricycle landing gear, not unlike the B-25 and fairly bristling with .30 Caliber (7.62 mm) machine guns. Unfortunately, while undergoing simulated "engine out" tests, the pilot lost control and the aircraft crashed. The pilot and crew escaped with minor injuries but the NA-40B was destroyed by fire and North American was disqualified, though the Army deemed the accident caused by pilot error and not by anything inherent in the design of the NA-40B. That left only 3 prototypes competing and shortly, one of these also crashed and burned (the Douglas 7B) and was disqualified, leaving less than half the original bidders still competing. The USAAC ruled no contest, and though Glenn Martin raised vigorous objections, new bids were ordered to be submitted in April, 1939. The result from North American was a dramatically updated NA-40, redesignated the NA-62. The design was much more streamlined with the rear of the "greenhouse" canopy neatly faired into the fuselage (instead of the "upside down bathtub" of the NA-40), forming a straight line from the top of the windshield to the tail assembly. On August 10, the design was accepted by the USAAC as the B-25 and ordered into production straight off the drawing board, something not often done with new aircraft. The B-25 was fitted with two turbo supercharged Wright R-2600 Cyclone radial engines and though the dash numbers changed and modifications were made to it, the supercharged R-2600 Cyclone was standard through the final production model which was the B-25J.

A landing gear, ready for assembly on a B-25 bomber, is rolled into place on the final assembly line of North American's Inglewood, Calif. plant. The NA-62 had been designed with a noticeable dihedral to the wings, as were the first nine B-25s. Starting with the tenth aircraft, the outer wing panels were made horizontal to enhance stability and this modification gave the Mitchell its distinctive frontal silhouette. A total of twenty-four B-25s were built before the B-25As came into production. The B-25A was a bit more suited for combat than its predecessor, having self-sealing fuel tanks and crew armor. However, most of the "A"s never saw combat but were used by the Army for coastal patrol and reconnaissance. Though the "A" had more armor, it was considered obsolete in a very short time because of its lack of provisions for self defense. A single .30 caliber (7.62 mm) machine gun was located at the waist and could be plugged into a ball socket on either side, another .30 cal. (7.62 mm) in the nose and one fired from a socket in the top of the fuselage. Because of the opinion that most attacks would come from the rear, the prone tail gunner operated a .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine gun. Forty B-25As were built by the end of production in August, 1941.

North American B-25 Mitchell At 8:20 AM on Saturday, April 18, 1942 the US Navy’s new carrier USS Hornet was approximately 650 miles (1,046 km) east of Tokyo, Japan, heading; 270°, speed; 20 knots (37 km/h). The original destination of the carrier was a launch point approximately 450 miles (724 km) east of Tokyo. But plans went awry earlier that morning when a Japanese picket boat (the "Nitto Maru" ) spotted them and sent a radio message to Tokyo. Though the message either was not received, or was ignored in Tokyo, the Americans had no way of knowing this. The aircraft were ordered launched immediately despite the fact they were 200 miles (322 km) further from the target than planned. Admiral William "Bull" Halsey aboard his flagship Enterprise had been informed of the message sent by the Nitto Maru. He couldn’t risk exposing the thin skinned carriers to a possible assault by a Japanese battlewagon, so he immediately flashed a message to the Hornet: "Launch Planes. To Colonel Doolittle and his gallant command Good Luck and God bless you". Intermittent rain squalls swept the flight deck and the sound of the Wright Cyclone engines warming up reverberated amongst the ships of Task Force 16. To an outside observer this would have appeared to be a standard naval combat mission except for two items: (1) This occurred a mere 4½ months after the Pearl Harbor disaster, and no one in their wildest dreams could have expected the US Navy to be able to attack Japan so soon. And: (2) These were definitely not naval aircraft thundering down the deck of the Hornet. They were US Army twin engine bombers! The Doolittle raid was carried out by sixteen B-25B aircraft. The "B" was built with the advantage of a degree of combat experience. Dorsal and ventral gun turrets, each housing twin .50 cal. (12.7 mm) Browning M2 machine guns were installed just behind the bomb bay. The .30 cal. (7.62 mm) was retained in the nose position. The tail gunner's position was eliminated and an observers station installed. Although the turrets adversely affected the top speed of the B, firepower was greatly improved.

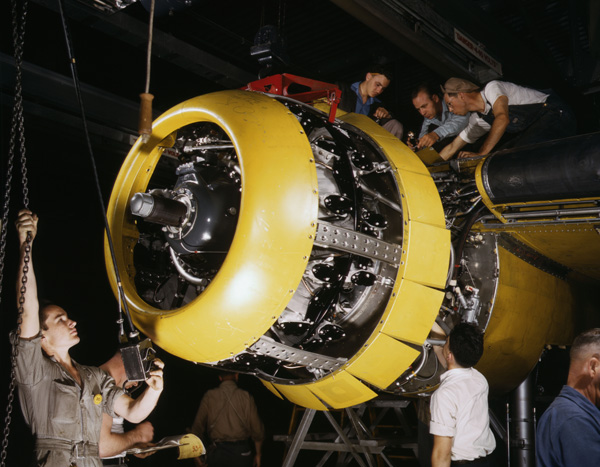

Under the close supervision of a foreman, a new engine assembly is installed in a B-25 bomber at North American's Inglewood, California plant. The B-25C was an accumulation of the combat experience and the suggestions of the crews. The navigator had a new sighting blister installed in the roof just behind the pilots greenhouse. The bombardier received considerably more firepower in the form of a flexible .50 cal (12.7mm) M-2 to replace the .30 cal (7.62 mm) , and a fixed, forward firing .50 cal (12.7 mm) in the nose. Thereafter, all machine guns on this and succeeding models were .50 cal (12.7 mm) M-2 Colt-Brownings. Improvements in the trusty Cyclone engines were made with the installation of Holley carburetors and air filters. A new 24 volt electrical system replaced the 12 volt of earlier models. There were anti-icing provisions for the leading edges of the craft and fuel capacity was increased. The "C" was in reality the first mass produced Mitchell with over 1,600 copies rolling off the production lines. Many of the improvements found on later models were first tested on a "C". The B-25D was identical to the "C", the only difference being the "D" was manufactured at the North American plant in Kansas City instead of the plant in Inglewood, California. There was only one copy each of the "E" and "F" models. They were both taken directly off the "C" production line and used solely for the purpose of testing new anteing and de-icing equipment. The first B-25G was serial #41-13296 which was taken off the "C" line and modified for the 75 mm M-4 cannon installation. The greenhouse nose was removed and replaced with a solid nose equipped with a pair of fixed, forward firing M-2 machine guns and the 75 mm M-4 cannon which ran under the pilots seat. Behind the pilot a gunner loaded, fired and extracted the empty shell casings. Twenty-one rounds were carried for the cannon. Armor was added to protect the gunner and the cannon rounds. Five of the "C"s were modified to the "G" configuration for testing before the production line started turning out "G"s. About 1,400 B-25Gs were produced.

Part of the cowling for one of the motors for a B-25 bomber is assembled in the engine department of North American's Inglewood, Calif. plant. The B-25H was considerably improved over the "G". The top Bendix turret was moved from behind the bomb bay forward to a position previously occupied by the navigator. The navigator was moved forward to the position of the cannon which was upgraded to the newer and lighter 75 mm model T13E1. The navigator acquired the duty of loading and firing the cannon in addition to his function as navigator and radio operator. Two additional M-2s were placed in the nose for a total of 4. The bottom turret was eliminated and replaced with an M-2 on each side in the waist position. Two more were placed in a power operated tail position. The B-25J reverted to the greenhouse bombardier nose of the "C" model, but with far more firepower. Some variants had as many as 14 forward firing M-2 machine guns in front and four more at various other stations in the craft. The 75mm cannon was removed and a bombardier was again added as the sixth crewman. B-25Js were by far the largest production run of the Mitchell bomber with more than 4,300 copies delivered before the war ended and production lines of the B-25 were shut down for good. Other aircraft were larger, faster, "prettier" and produced in greater quantities. But none could surpass the colorful career of the North American B-25 Mitchell bomber. |

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| North American B-25J "Mitchell" Medium Bomber | |

| Dimensions: | |

| Wing span: | Wing Span: 67 ft 7 in (20.59 m) |

| Length: | Length: 51 ft (15.55 m) |

| Height: | Height: 16 ft 4 in (4.98 m) |

| Wing Area: | 610 sq ft (56.67 m²) |

| Weights: | |

| Empty: | 19,530 lb (8,858 kg) |

| Gross: | 26,122 lb (11,848 kg) |

| Maximum T/O: | 35,000 lb. (15,876 kg) |

| Performance: | |

| Maximum Speed: | 285 mph (458 kph) at 15,000 ft (4,572 m) |

| Cruising Speed: | 230 mph (370 kph) |

| Service Ceiling: | 24,200 ft (7,376 m) |

| Normal Range: |

1,350 miles (2,172 km) with 3,000 lbs (1,360 kg) of bombs |

| Maximum Range: | 2,200 miles (3,540 km) with ferry tanks |

| Powerplant: | |

| Two 1,700 hp (1,268 kW) R-2600-29 Wright "Cyclone" 14-cylinder radial engines. | |

| Armament: | |

|

Eighteen Browning .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns. Up to 3,200 lbs (1,451 kg) of bombs | |

©Earl Swinhart The Aviation History Online Museum. All rights reserved.

Created May 1, 2001. Updated June 9, 2014.