| Curtiss OX-5 |

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

| |

| ||

|

|||

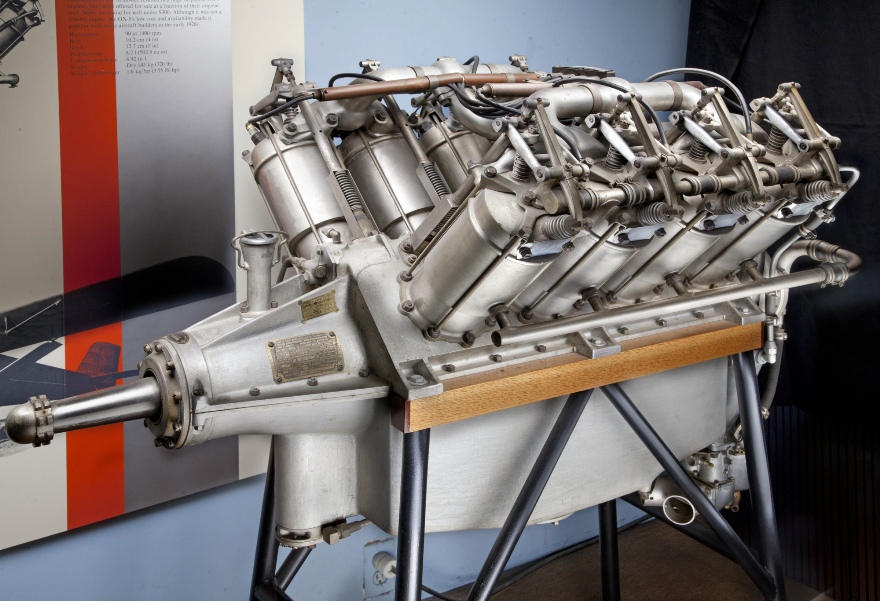

| The OX-5 was the last in a series of Vee engines designed by Glenn Curtiss that began in 1910. It was a pre-war engine and although obsolete by World War I, it was still put into mass production and was the mainstay of the American wartime training program. There weren’t too many options at the time for the US Army Air Service and the only good domestic trainer available was the Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, designed around the OX-5. | |||

| The original OX-5 steel and copper parts were nickel plated, making it a beautiful engine in its classic form. It had an aluminum wet-sump crankcase and separate steel cylinders with brazed copper-nickel alloy (Monel) water jackets. The cylinder heads were attached to the crankcase using X-shaped tie-downs on the top of the head, attached to the block via four long bolts. Fuel was carbureted near the rear of the engine and piped to the cylinders via two T-shaped pipes. The overhead valves were actuated by pull and push rods. There was only enough room for one rocker arm, so the exhaust valve used a normal pushrod that was inside a tubular yoke that pulled the intake valve open. The benefit of this configuration gave the OX-5 overhead valves, which delivered better results in breathing, combustion and power output.1 | |||

|

It was a high maintenance engine and the valve mechanism had to be lubricated approximately every five hours. This was unlike the

Hispano-Suiza

engine where the valve mechanism was entirely enclosed in an oil tight compartment and continuously lubricated. Grease was needed for the rocker arm bushings, engine oil was used for the valve springs and pull down straps, Marvel Mystery oil was used for the valve guides and a spray lubricant was used for the rocker arm rollers. Most airplanes would carry several hours of fuel, so the limiting factor would be the lubrication of the engine.2

During cold weather the engine was hard to start. The amount of oil in the crankcase caused a lot of drag on the engine, so it was common practice to drain the oil and store it inside overnight to keep it from thickening. |

|||

|

|||

|

The OX-5 was rated at 90 hp and turned at a leisurely rate of 1,400 rpm. It was a slow turning engine and the idle speed was an even slower 450 rpm. Despite the engine’s slow speed, it had tremendous torque and would normally turn a large prop on the order of 100 inches. Propellers are more efficient the slower they turn and for the high-drag

Curtiss Jenny, a slow turning, large propeller would be more efficient for producing thrust. The technology at the time called for 1,800 rpm as the prudent maximum propeller speed with the absolute racing maximum at 2,000 rpm.3

During the war, thousands of OX-5 engines were produced and they saturated the market during the 1920s. In 1917, new Curtiss Jennys were sold to the government for $8,160, but by 1919, a reconditioned Jenny purchased from the Army by Curtiss were selling for $4,000 and OX-5 engines were selling for $1,000. By the mid 1920s, the price of a rebuilt Jenny had dropped to an average price of $2,400. Towards the end of their careers, Jennys could be bought for as little as $500 among private owners, and by 1928, an unused OX-5 could be purchased for a standard price of $250. With such a glut of surplus military aircraft on the market, it was difficult for manufacturers to compete with the production of new aircraft for the civilian market.4 While the OX-5 had a reputation as being unreliable, this characterization may not be justified, considering the times. With the glut of aircraft on the market, machines could be purchased so cheaply that many would up in the hands of inexperienced flyers and not maintained properly. There was no type certification or FAA required inspections at the time. The cooling system was prone to leaking. There were 64 connections for the water system and with so many hoses and connections, inspection and replacement before failure would have been fairly expensive. Fuel strainers were nonexistent at the time as well as engine air filters and carburetor heat to prevent icing. Carburetor icing wasn’t understood at the time. The ignition system left something to be desired. There was only a single ignition system and the Dixie magnetos were poorly designed. The engine could be improved with the installation of a Bosch or Splitdorf magneto, but these magnetos were unavailable during the war. Modern sources claim that if maintained properly, the OX-5 was as reliable as any other engine during this period. In any event, due to the availability of airplanes and engines at such a modest price, many people got the chance to fly that might not otherwise have had the opportunity. One such person was Charles Lindbergh who owned a Curtiss Jenny powered by a Curtiss OX-5. | |||

| Specifications: | |

|---|---|

| Curtiss OX-5 | Date: | 1910 |

| Cylinders: | 8 |

| Configuration: | V, liquid-cooled |

| Horsepower: | 90 (67 kw) |

| RPM: | 1,400 |

| Bore and Stroke: | 4 in. (102 mm) x 5 in. (127 mm) |

| Displacement: | 503 cu. in. (8.24 liters) |

| Weight: | 390 lbs. (177 kg) |

Endnotes:

|

1. Herschel Smith. A History of Aircraft Piston Engines. Manhattan, Kansas: Sunflower University Press, 1993. 46. 2. Chad Wille. A Delight of Old Engines; The Curtiss OX-5. To Fly Magazine, 2000. 3. Hugo T. Byttebier. The Curtiss D-12 Aero Engine. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972. 56. 4. Murray Rubenstein & Richard M. Goldman. To Join with Eagles. A complete illustrated history of Curtiss Wright aircraft from 1903 to 1965. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1974. 39. |

Larry Dwyer. © The Aviation History On-Line Museum. All rights reserved.

Created February 24, 2013. Updated October 12, 2013.